- THE CHILD SAVERS – CHILD RESCUERS

Let’s return to the 1880s where we find a crusade for reforming dissolute urban working-class family life through Christian charity—middle-class morality and concern for social stability. The tropes of child as victim and child as threat intersected.

The Scots Church Children’s Aid Society explained: children must be rescued

from squalor and misery; from unloving parents; from sin and shame. Oh how cruel and heartless some of these fathers and mothers are![1]

If the young are allowed to grow up in the midst of vice they must necessarily be vicious...[2]

Another pattern in non-government child welfare emerged:

a committee of leisured upper-class women financing and overseeing the small salaried staff that had direct contact with the clientele.[3]

In 1881, the Scots’ Church District Association[4] appointed a Miss Selina Murray MacDonald Sutherland, a nurse residing at 220 King Street, West Melbourne as their Lady Missionary. Miss Sutherland was to visit ‘house to house, and also in the gaol and different hospitals’. Before long, she was devoting herself full-time to neglected and destitute children.[5]

Miss Sutherland was a powerful, love-her-or-hate-her figure in the welfare field. She was the first person authorised under the Neglected Children’s Act 1887 to arrest children she deemed to be neglected. She and other child rescuers had powers ‘which paralleled those of the police‘.[6] A biographer pictures Miss Sutherland

fearless in her search for children in back streets and alleyways, brothels and gambling houses.[7]

In 1890, the Association, now called the Presbyterian and Scots’ Church Neglected Children’s Aid Society, purchased a house at 149 Flemington Road, North Melbourne and called it Kildonan—sometimes referred to as the Kildonan Receiving House because it was envisaged that it would act as a reception centre for young children waiting to be boarded-out in private homes around the suburbs and especially in rural Victoria.

Meanwhile, back in La Trobe Street in 1894 an acrimonious rift occurred, which was both personal and ideological. There had been rumblings about taking children who were voluntarily surrendered to the Society by their parents as contrasted with those who were removed from ‘unfit’ parents under legal guardianship. [8]

The hard-line view was that parents had a duty to care for their children, no matter how hard-up they were, and neither the church nor the state should relieve them of that duty. Moreover, it was one thing for Miss Sutherland to upset the church elders by helping non-Presbyterian children, or boarding-out Presbyterian children with non-Presbyterian families.

But it didn’t do to accuse male office-bearers of the church of making money out of prostitution. Selina and her Ladies’ Committee resigned in a very public row in 1894.

Miss Sutherland was resilient and politically well connected. The Society included Victoria’s Chief Secretary, Alfred Deakin, the member for Essendon and Flemington, who was to become a three-time Prime Minister of Australia, and Alexander Peacock who was premier of Victoria at the time of Federation.

She soon formed a new Victorian Neglected Children’s Aid Society and was its official Agent. She and her children marched down to another building further down La Trobe Street.

The Society worked from La Trobe Street from 1895 until 1901 when it bought Ayr House, a mansion on the corner of Leonard Street and Royal Parade, Parkville—built by another North Melbourne identity, James Ferguson formerly of Little Curzon Street. International House now stands on the site.

It has been known variously as the Parkville Home, Sutherland House (from 1905), and Swinburne House (from 1957 after Mrs Swinburne who had been President from 1913 to 1957).

The Parkville Home and Kildonan ran along the same lines. They found ‘good families’ (preferably in the country) that would take the children as their own. These boarded-out children remained under the legal control of the organisation and were visited by Agents like Selina Sutherland or members of local Ladies Committees, although supervision of the children was often problematic and some of the placements were known to result in ‘neglect, and unkind or injudicious treatment by foster-parents’.[9]

Both Kildonan and Parkville also accommodated older girls who had been returned from service—i.e. those who had been sent to service with a family but had been returned, either because they had not been deemed satisfactory, or because they had become of working age, too old for the families to receive the weekly payment from the government.

Over the years it became difficult to find enough good homes. The State government was reluctant to pay foster families adequate allowances for taking a child—nothing’s changed there! This became an especially acute problem in the years of the Great Depression from 1929.

In 1908, the Parkville Home in Leonard St accommodated around 70 children, but in that year staff and some of the girls made serious allegations against Miss Sutherland of drunkenness, cruelty and negligence. She was sacked (again).

She moved back to the La Trobe Street Receiving Home, which was rented in her name (but paid for by the police)[10] and within months, she and her supporters had formally constituted ‘The Sutherland Homes for Orphans, Neglected and Destitute Children’ with a committee of prominent citizens, including some of her old committee. In November a government inquiry into her dismissal, instigated by her critics, appeared to have vindicated her. It’s a bit grey!

The new society attracted generous support. In April 1909 she was gifted a 40 acre farm and house at Diamond Creek. She planned to take the girls from the city to Diamond Creek, but on the day scheduled to move in to the new property in Diamond Creek, 8 October 1909, Miss Sutherland died suddenly of pneumonia.

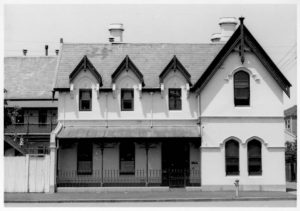

Notwithstanding her death, Diamond Creek went ahead. Her Committee decided that the La Trobe Street building was unsuitable as the Receiving Home for Sutherland Homes and, in 1911-1912, built a new Home on land at 28 Drummond Street, Carlton. From there, children were sent to the Home or Homes at Diamond Creek.

Rounding off what happened to the ventures Selina Sutherland pioneered is useful because it gives insights into the changing philosophies of child welfare. The old Kildonan house accommodated up to 30 children. Extensive renovations in 1912-14 took its capacity up to 48 children.

In 1937, Kildonan transferred operations from North Melbourne to Elgar Road, Burwood. Encouraged by the movement away from large warehouses for children in favour of a cottage system supervised by rostered staff, and then later still family group homes dotted around the suburbs. From September 2001, the agency ceased all residential care activity and in 2007 the organisation became Kildonan UnitingCare and, this year, simply as Uniting.

Meanwhile, the old Kildonan house at 149 Flemington Road, Flemington is now Mcauley Community Services for Women, offering medium term, supported accommodation program for women aged over 25 years who may have a mental illness – but unaccompanied by children.

The Victorian Neglected Children’s Aid Society changed its name again in 1920, to the Victorian Children’s Aid Society, but it continued with its program at Leonard St Parkville until it, too, was caught up in the deinstitutionalisation movement.

In 1966 the Society moved its home and headquarters from Parkville to a property at Black Rock (Somers House, a former CWA holiday home).[11] It sold the Parkville property to the University of Melbourne to pay for its developments in Black Rock and subsequently developed cottage homes, and group homes. In 1991 it became Family Focus and in 1992 merged with other children’s organisations to form Oz Child-Children Australia.

The Sutherland Homes Receiving Home in Carlton was sold in the 1950s. Diamond Creek continued operating until 1984 when they merged with Berry Street, now one of Victoria’s biggest and most diverse providers of children’s services.

By the 1980s most of the old institutions had closed. Many became multi-purpose welfare agencies again; some were converted to aged care facilities.

———————————————————————————–

[1] Home for the Homeless, Journal of the Scots’ Church Children’s Aid Society, Vol. 1, No. 2, July 1892, p. 1.

[2] Qu. In Scott & Swain 1992, p. 5.

[3] From Dark to Dawn, Vol. 1, No. 1, 1 March 1898 qu. In Scott & Swain p. 30.

[4] The Presbyterian Society for Neglected and Destitute Children was formed in 1893 and was renamed the Neglected Children’s Aid Society

[5] In addition to newspapers of the day, I have drawn on the Find & Connect website, Marjorie Robinson, Kildonan: One Hundred Years of Caring, The Council of the Uniting Church, Melbourne, 1981; Della Hilton, Selina’s Legacy: From VCAS to Oz Child, OzChild, Melbourne 1993; Nancy Groll, Sutherland: A century of caring for children, Berry Street, Melbourne, 2000; Dorothy Scott & Shurlee Swain, Confronting Cruelty: Historical Perspectives on child protection in Australia, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 2002; Sharon Lane (ed.) Kildonan: 135 Years, Closer, Bolder, Stronger, Kildonan, Melbourne, 2016.

[6] Shurlee Swain, ‘The state and the child’, Australian Journal of Legal History, vol. 4, 1998, pp. 57-77.

[7] Ruth Hoban, Sutherland, Selina Murray (1839-1909), Australian Dictionary of Biography, 1976, on line at: http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/sutherland-selina-murray-4674

[8] ‘Miss Sutherland and her Committee Resign’, The Argus, 17 November 1894, p. 8.

[9] Report of the Inspector Industrial & Reformatory Schools for the Year 1875, Melbourne, 1876, p. 3.

[10] Nancy Groll, Sutherland: A century of caring for children, Melbourne, Berry Street, 2000, p. 8.

[11] Somers House was soon renamed Swinburne House. Hilton, p. 149