UPDATE

Dot Wickham and I are working on a book that deals with the Homes mentioned on this page – AND LOTS MORE!

I’ll post more information when we get a bit closer to publication.

—————————–

Little-known Children’s Homes in Ballarat

This is an ongoing piece of research into the Homes established in Ballarat by Mrs Elizabeth Nevett. All the information is subject to review (as at January 2019).

These two Homes – well, three if you separate the Laundry from the Cottage of Mercy – are somewhat unusual in the context of the large institutions that existed in Ballarat such as the Ballarat Orphanage, Nazareth House and St Joseph’s Orphanage….read on.

The Bond Street Home

This was a small privately-run, non-denominational Home situated at 56 Bond Street, Golden Point, Ballarat near Llanberris Reserve. From newspaper reports, it opened in 1898.

Mrs Elizabeth Nevett (1849-1944) was the President of a Committee of Management throughout its lifetime. Mrs Nevett, from a well-to-do family, was the wife of a leading Ballarat lawyer. Mr and Mrs Nevett were both prominent in public affairs in Ballarat and, jointly and separately, supported a range of charities. Mrs Nevett was the President of the Ballarat branch of the Australian Women’s National League (AWNL).[1]

Records of the Bond Street Home cannot be located at this time. It is possible that no official records were kept – or if they were, they were not archived when the Home closed in 1925. For information about the Home we have to rely on the occasional reports in the local press – Ballarat Courier and Ballarat Times. Thank goodness for the wonderful research tool called Trove.

It is not clear why the Bond Street Home was set up when a large Orphanage was already in existence in Ballarat East – not to mention the equally large Nazareth House (a Catholic orphanage opened in 1888) and the Canadian Rescue and Children’s Home (a small Home run by the Town & City Mission from 1897).

The boarding-out policy that allowed children to be placed in foster homes (sometimes with their own mothers) was an alternative in Ballarat (See e.g. Ballarat Star 25.12.1914, p. 11).

Mrs Nevett was not enamoured of the boarding-out system partly because she saw it as a commercial arrangement that allowed mothers to shirk their responsibility. Further, she considered a small Home like Bond Street offered a more homely atmosphere with assured values – a ‘real home life’ that paid foster mothers could not match (Ballarat Star, 12.12.1914, p. 2).

The relationship with the Orphanage was ambivalent. Appealing to members to donate to the Bond Street Children’s Home in 1899, the Chairman of the Ballarat Stock Exchange, JD Woolcott, felt it necessary to stress that ‘the institution in no way clashed with the Orphanage’. He pointed out that the Home frequently took in ‘little ones whose parents were living, but whose surroundings were such that it was to the interest of society that they should be rescued from them (Ballarat Star 21.2.1899, p. 2).

Yet, there were obvious tensions between this small institution (never more than 15 children at a time) and the large Orphanage (which at its peak had 230 children). When presenting the Annual Report of the Children’s Home for 1913, Mrs Nevett stated that ‘the government had withdrawn the small grant they gave us for many years, because we refused to amalgamate with the Orphanage’ (Ballarat Star 26.8.1913, p. 2). The basis of this refusal is not stated.

It is interesting to note that Elizabeth Nevett’s husband was never a member of the Board of Management of the Orphanage when men of his prominence in Ballarat’s civic affairs were enthusiastic to play that role. (Women could join a Ladies Committee, but Mrs Nevett never did join.) Despite considerable publicity given to financial donors, the Nevetts made no substantial contribution to the Orphanage – the legal firm of Nevett & Nevett contributed its first token guinea in 1909 – and that was their standard annual donation thereafter.

It is possible to hypothesise that Mrs Nevett founded the Children’s Home as her personal project – one she could govern and control without interference. She was the driving force: she

- raised funds and marshalled in-kind support,

- selected its staff,

- signed off on every annual report, and

- was the public voice of the Home in the local press.

She was a devout Christian and brought the values of the Mothers’ Union of Ballarat (she was its Secretary in the 1890s) to her ‘rescue’ work with children. In 1909, Mrs Nevett was Gazetted as a Probation Officer for the Neglected Children’s Department (Victorian Government Gazette 3.11.1909, p. 4810).

Mrs Nevett reported that Mrs Simpson, Matron for ten years, who retired in 1913, had served the Home since the children had been infants. And the children were

‘now getting to the age of usefulness, and desire to develop their garden and make it productive…’

This suggests that a proportion of the children had been long-term residents (Ballarat Star 26.8.1913, p. 2). Mrs Crowe took over as Matron from Mrs Simpson in 1913 and was much praised: Mr Hauser, the Principal of the local Mt Pleasant Primary School, reported that the children were clean and well dressed and attended school regularly (Ballarat Star, 7.11.1914, p. 11)

The War which began in 1914 created competing priorities for Mrs Nevett and the middle-class women who had previously volunteered their efforts on behalf of the Home. The Annual Meeting was delayed by seven months in 1915 and again in 1917 ‘because of the pressure of other work’, notably patriotic work that ‘overshadowed the small local charities’. At the same time, the Home was beginning to experience financial stress (Ballarat Star 10.3.1916, p. 4; 7.3.1918, p. 2)

Mrs Allen replaced Mrs Crowe as Matron in 1916 but the numbers of children slowly dwindled – by 1920 there were just seven including two boys working at the local woollen mill. Perhaps the boarding-out scheme was having an impact. In Ballarat in 1920, the local Inspector of the Neglected Children’s Department visited 538 boarded-out children in foster homes or in their own homes between August and October alone (Ballarat Star, 25.12.1920, p. 7)

Towards the end of 1922, Mrs Nevett decided she and her lady friends were not now able to continue its operations. It was time to close the Home. Mrs Nevett, through her husband’s legal agents, asked the Supreme Court for a ruling on the distribution of assets –

- two blocks of land, valued at about £1 000 on one of which the home was built, and

- money on current account amounting to £104.

It was noted that the Ballarat Town and City Mission carried on similar work in Ballarat and was willing to receive the assets and apply them to similar work. The Court so ruled, providing that the sum of £100 be gifted to the Free Kindergarten. The Ballarat Star (10.2.1923) reported that 56 Bond Street was up for auction.

♣♣♣

The Children’s Home Laundry and Cottage of Mercy

This other institution was closely linked to the Children’s Home. It was set up by Mrs Nevett in 1898 or 1899 initially in a house on the corner of Dana and Raglan Streets, Ballarat.

The object of the institution was

‘to assist women upon whom society frowns to earn a living, and…prevent the necessity for boarding out children of shame.’ (Ballarat Star 31.3.1899, p. 2).

The ultimate goal was to train the ‘children of shame’ to earn their own living. The sparsely furnished laundry was managed by a small committee of women, but Mrs Nevett made a successful appeal for furniture, blankets and bedclothes, and cast-off clothing. ‘God’s work must prosper,’ was her keynote (Ballarat Star, 5.8.1903, p. 4).

In 1903, the Children’s Laundry moved to ‘Marlborough House’, in Victoria Street, Ballarat while the Cottage of Mercy moved to ‘Melrose’, in Eyre Street near the Benevolent Asylum. A Mrs Clennel (a former Salvation Army Officer) was in charge of the laundry and a Mrs Simpson was Matron of the Cottage of Mercy (although there is some confusion about whether Mrs Simpson was also Matron of the co-existing Bond Street Children’s Home).

An observer reported:

‘…it is not that children do the laundry work, but that the mothers do the work and the little ones do the looking on.’

The women in question, he reported, were those

‘not admissible to the Maternity Home…poor lasses who have been too trusting, and allowed themselves to be led astray…’

There were about a dozen ‘girls’ and their babies in residence at that time but over the previous five years some 50 ‘young girls and babies had been looked after and cared for’ (Ballarat Star 6.2.1903, p. 3).

In 1908 Mrs Nevett was compelled publicly to deny reports that the ‘girls’ were not allowed religious freedom. The Home was ‘strictly unsectarian’, and the residents could attend any church of their choice. She, herself, had given simple religious instruction,

‘the sole object being to try to awaken them to the knowledge of the All Father, the God of love, and to try and induce them to live higher and better lives…’ (Ballarat Star 23.11.1908, p.4)

The following year, Mrs Nevett would have been pleased with the unanimity of a public meeting on juvenile morality in Ballarat – in particular, neglectful parents allowing young girls on the streets at night and being thus placed in danger of ‘acts of brutality and immorality’. It was Mr Nevett who successfully moved for the formation of a council of 36 clergy and laymen (no women) to implement the range of resolutions carried at the meeting (Ballarat Star 17.2.1909 p. 1).

In 1910, Mrs Nevett reported that the government was

‘withholding State aid… because our Homes receive so little local support’.

She thought this ‘most unjust’ because they were amply supported by volunteers and in-kind support. Nevertheless, she was determined to push on. She had even purchased a block of land in Lydiard Street north where she intended to build the training laundry. Meanwhile, she reported, the Bond Street Home was free of debt (Ballarat Star 15.10.1910, p. 4).

However, all was not smooth sailing. In 1914, Mrs Nevett informed the public that the laundry was closing. She argued that

‘young women prefer to board out their infants, and are encouraged to do so by the State…’

And because the State had ‘become the foster mother’ relieving parents of all responsibility, maternity homes were no longer necessary. Tellingly, she went on to claim that the Wages Board was also making it impossible to make a profit from the laundry. She did not refer to the competition from the established laundry run by the Town and City Mission where ‘worthy women’ who had been paid a wage – although it too fell on hard times and was sold off in 1914 (Ballarat Star 14.7.1914, p. 3)

In lieu of a laundry, Mrs Nevett revealed her new plan for the Lydiard Street block: she would build a training home for children. Collectively, there were 13 children in the Bond Street Home and the Cottage Home (Ballarat Star 4.11.1911, p. 3). That goal was never achieved.

On 29 November 1944, Elizabeth Nevett (nee Dowling) passed away at her home in Ballarat, aged 93, living not quite long enough to see her beloved AWNL merge with the Liberal Party of Australia. But she may well have listened to the radio talk by the Party’s leader, Robert Menzies, in 1942:

…to say that the industrious and intelligent son of self-sacrificing and saving and forward-looking parents has the same social deserts and even material needs as the dull offspring of stupid and improvident parents is absurd.[2]

Having assisted ‘women upon whom society frowned’ and provided a Home to their ‘children of shame’, Mrs Nevett perhaps would not have fully agreed with Menzies’ sentiment.

Footnotes

[1]The Australian Women’s Register reports: ‘The Australian Women’s National League (AWNL) was a conservative women’s organisation established in 1904 to support the monarchy and empire, to combat socialism, educate women in politics and safeguard the interests of the home, women and children. It aimed to garner the votes of newly enfranchised women for non-Labor political groups espousing free trade and anti-socialist sentiments, with considerable organisational success.’ (http://trove.nla.gov.au/people/598652?c=people)

[2] Robert Menzies, ‘The Forgotten People’, Speech broadcast on 22 May 1942, reprinted in Sally Warhaft (ed.) 2004 Well May We Say…The Speeches that Made Australia, Melbourne, Black Inc: 155.

♣♣♣

RECORDS

The Subject Child (21 February 2015)

(Based on a true story, but all names have been changed)

Josie grew up in an ordinary family with her sister Bev and brother Colin. At her 21st birthday party, many years ago now, her parents set up a display of snaps from a babe-in-arms to her graduation day. They plundered the stack of albums that recorded Josie’s ever-changing childhood. As well, they also created a ‘This-is-Your-Life’ display of her many school reports, certificates and awards, sporting trophies, holiday postcards, and even vaccination certificates.

Josie wanted to die: how could they? Then she noticed that her friends seemed really interested in this exhibition of her life. They were soon swapping jokes about first boyfriends, clothes they wouldn’t be seen dead in now, secrets they had kept from their parents.

Amazed that her parents had kept so much stuff from her childhood, Josie was tickled pink that they had gone to such trouble to put it all together – with love and pride. At 21, Josie was a self-assured young woman: she loved her family and felt loved in turn; but all the same she looked forward to leaving home knowing that some part of her family would always go with her and some part of her would always stay with her family even when she married Geoffrey and moved interstate for a while.

Last year, at her 50th, a tribe of children – two of her own and five nieces and nephews – presented her with a new laptop, a special gift from the whole family, and competed with one another to help cut the cake and eat it too. Grandparents buzzed around like bees blissed with nectar. The technology had changed, some of the photos had now faded, but Josie now enjoyed the role of family archivist.

♣♣♣

Josie’s friend and neighbour, Pam, was put in an orphanage at five years of age. Her sister Jenny, nearly two, went to the nearby Babies Home; but their baby brother, Bobby, stayed with their Mum. At least, that’s what they were led to believe in the years that followed. When she turned four, Jenny graduated to the orphanage although not to the same dormitory as Pam. When she left school at 15, she and a change of clothes in a small brown suitcase were despatched to a town in the Wimmera to be ‘in service’ as a domestic. A couple of years later, Jenny was sent with her brown suitcase to a farm near the Murray, again ‘in service’. Nobody thought to send them to the same area. Or even to tell the one where the other was now living.

On first leaving the Home, Pam had tried to keep in touch with Jenny but her letters were never answered. Were they even delivered? When she called at the Home a few years later they told her that no one knew where Jenny was now. She had absconded from her job and the notice in the Police Gazette didn’t get a result.

Pam had no idea where their brother Bobby was now. She had not seen him since he was a baby. She wouldn’t know him if she ran into him on the street. Come to that, Pam wasn’t sure if she would recognize Jenny if they bumped into each other. It crossed her mind that Jenny had found their mother and was living with her and Bobby who would be almost a grown man by now.

Unlike her friend Josie, when Pam turned 21, not a soul knew. She told anyone who asked the date that she hated birthdays. In fact, she had never had a birthday party – nobody did in the Home. She was tempted to confess all this to her boyfriend at the time, but her head flashed warning signs: he and her handful of other friends would drop her if they knew that her parents had dumped her all those years ago.

She continued to carry her childhood secret for many years. Her self-esteem was so low that she had never told Phil, the man she loved and had married. When their children, Sally and Johnny, came along Pam went out of her way to make sure their birthdays were celebrated with gusto. Phil was puzzled when she said she didn’t know how to arrange a birthday party. He knew her parents had been very ill for most of Pam’s childhood, far too sick to buy presents for her. Phil understood. He laughed it off and just got on and organised the first party. Pam soon got the hang of it. Sally and Peter would get everything that she never had as a child – and the same at Christmas – they would want for nothing.

It came as a huge relief the day she confided in someone at last. It was as if by accident over coffee with Josie. She knew she could trust Josie: the nearest she would ever get to having a sister again. Josie set the photo album on the table and opened it to the page with the sticky note.

“No, they aren’t my little darlings. The little girl in the tartan school tunic is me. And the toddlers holding her school satchel? Colin and Bev.”

They laughed at the family likeness. “All the good looks come from Geoffrey,” Josie declared in mock modesty. “You want to see more? Look in the cupboard under the stairs,” Josie explained, and recounted the story of her party for her 21st.

Pam felt the duty to reciprocate, but the thought hung uneasy in the air. Was it time? First a confession: she had plenty of photos of her children, but not a single shot of herself as a child. That could not go unexplained. Who would have a camera in an orphanage? Pam tried to brush aside her embarrassment, but the redness burst out from her neck and rushed up her cheeks.

“But nobody chooses to live in an orphanage,” Josie remarked. “Come to that, nobody chooses the family that brings you into the world. What have you got to be ashamed of?”

“It’s all the awkward questions,” Pam replied. “What happened to your father? Why did your mother give you up? Did they come and visit you? Do you see your parents now? Why not? I’d feel like a goose: I can’t answer any of these questions. I don’t know anything about why I was put in a Home. I suspect that our father had cleared out, but that’s just a guess. I don’t know what’s become of my mother and Bobby. And now Jenny, simply gone. And now…and now…another confession. I’ve lied to Phil all the time we’ve been together. Well, not exactly lied; just not truthful with him in the beginning…and he gained the wrong impression…then the years pass…and you just keep everything a little obscure.”

♣♣♣

On the day Pam turned 50, she decided she had had enough of hiding her childhood past from her own family. In her words:

“I took Phil to the local pub – the only place where we could be private and in public at the same time – and spilled the beans. I was so nervous, but once I started, it all tumbled out. Growing up in an orphanage when I wasn’t an orphan. My father, the mystery man; my mother; Jenny and Bobby. Not that it took long. I had so few facts to tell. The Home people never told me anything. In the end, you just gave up asking when your parents were coming to get you. Or whether Bobby could come and live with us too. They told me my Mum didn’t want us any more. I just gave up and accepted things as they were. After a few years in the Home, I almost forgot that Jenny was my sister. There were too many other children – great friends some of them and others who terrified me. I can’t talk about what happened there.

“Phil was astounded. He said he knew there was something I had been holding back all the years we’d been together.

‘“You must tell the children,’ he said. ‘They will be so proud of you and what you’ve made of yourself. They’ll want to know your story.’

“Phil convinced me. ‘You can’t live the rest of your life not knowing where your sister and brother are,’ he said. ‘Your children have an auntie and an uncle somewhere they’ve never met. Perhaps cousins too. There must be somewhere you can find what happened back when you were babies, and where they are now.”’

♣♣♣

When she wrote to the Department, Pam was given the runaround at first. The Department held only parts of the files. If she were patient, she could get access to most of what they had in their archives; but she would also have to go to the organisation that ran the orphanage. She didn’t like that: she had been brutalised and humiliated in that place and couldn’t bear the thought of going back to ask a favour.

Then she found the orphanage had shut down and a different kind of agency had taken over the records. The Department gave her a head start on who to contact, but would give no guarantees about whether they had kept her records even though the Department had sent her there as a state ward and contributed to the running costs of the place. She thought the Department should have had a copy of everything the orphanage wrote about her.

It took almost a year to get the dossiers but, even when she combined their contents, her childhood was a very short story indeed. Pam asked Phil to go through the documents to see if she had missed anything about her parents, or Jenny and Bobby – and how she might make contact with them. She found nothing except fleeting mentions but occasionally there were sections blanked out that might have been about her mother or Jenny. The Department told her they were about another person – and ‘the third party rule’ applied. What was this third party doing in my file? she asked; it might be a clue to our family’s story. But this was a no-go zone. She wondered why they had kept these records all these decades. What good were they doing taking up space in an archive if the person concerned was not allowed to read them, in full?

She asked the Department if she could have a look at Jenny’s file but they said that was illegal, a breach of privacy. If she got Jenny’s consent, they would reconsider. How could she get Jenny’s consent if she didn’t know what had become of her? So while she gained some understanding of why she was made a state ward, she longed to know her mother’s side of the story, to know why her father had deserted her and abandoned his family. The hope that the childhood records would provide a means of reconnecting to her family now seemed naïve.

Putting that all to one side, Pam was struck by the gap between what she found in the records and her life as a child. There was nothing about the day-to-day life of the orphanage. None of the things that stuck in her mind were there: the vicious fights, the cruel punishment for wetting the bed, the weevils in the porridge, the vile Epsom salts every Saturday to clean out your system. She found nothing about cleaning your teeth with salt, sharing bath towels with other girls, mending tunics handed down from girl to girl year after year, the toilet doors being taken off so staff could keep their eye on you even while you wiped yourself clean.

She expected, at least, to find records about her schooling and her illnesses. Some years she remembered her teachers gave her reports to take home to Matron, but these were never kept, it seems, just as they were never discussed with her at the time. She remembered at least two occasions when she was very ill – she thinks German measles, maybe the flu, but there was nothing in her records. Her doctor had been incredulous that she could not tell her what vaccinations she had had as a child. If anything was ever written down about her health, it was not included here.

Most of the pages seemed written by bureaucrats to tell other bureaucrats something they felt was important. Most of it, Pam felt, was trivial, just routine. No one seemed to care if her name and its spelling were just plain wrong. Her date of birth was incorrect on two occasions. If they were sloppy about that, how could she rely on their claims about her mother? It was obvious that they never intended, or envisaged, that one day she – ‘the subject child’ – would read what was written about her. They could be as rude as they liked adding judgmental comments about her mother without any reference to the facts. Memorialising gossip as perpetual truth.

Some notes made her angry, including an inspector’s comment about what a happy girl she was – and ‘making good progress’. She would swear she was never asked if she was happy. No inspector ever talked to her. She was never invited to contribute anything to the record that was being made about her. She wanted to scrawl over some pages: “Lies, all lies!”

If she were ever going to connect with her family again – and find the authentic story she needed to know – she would have to follow other footprints.

♣♣♣♣♣♣♣♣♣

♣♣♣♣♣♣♣♣♣

PHOTOJOURNAL

The following photo essay is an example of something I have always wanted to do. I have found in the last few years that Facebook and other social media have been a more convenient platform. However, I might get back to this form sometime in the future.

Remembering through the pain

Human Rights and Memory: Fourth Annual Conference of the Dialogues on Historical Justice and Memory Network, University of Lund, Sweden, December 2014

Frank Golding, 19 December 2014

I travel to Sweden via Hong Kong, England, Norway and Denmark to speak on the theme of the rights of the child – or, more to the point, the violation of rights when a child is abused. A network within the conference has taken up that particular focus and I am also to address the members at a workshop on the day before the main conference kicks off.

The conference program confirms that people memorialise breaches of human rights and crimes against humanity in many nations and in many forms. Scholars and activists will talk about a wide range of atrocities across the globe: in Latin America, Japan, Cambodia, Albania, Timor-leste, the Middle East, the US, Africa, China. The list seems endless. And of course the Holocaust, the interpretation and memorialisation of which is still a contested matter six decades on.

Experts will discuss the different ways atrocities are remembered – collectively and in particular communities; who remembers them; why some atrocities are remembered and others seem soon forgotten; how human rights abuses are communicated in literature, film and art, in museums, in education programs, and now even in video games.

They will discuss cosmopolitanism and transnational memory as well as grass-roots initiatives, trying to connect collective memory with people’s lived experience. There will be discussions about truth and reconciliation, reparations, and retributive justice.

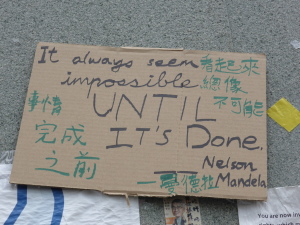

The leisurely journey to Sweden is broken at Hong Kong. If ever there was a living example of human rights being abused, it’s here on the streets where thousands of young people demonstrate brave resistance to China’s restrictions on the right to vote for freely chosen political candidates.

You do not need to be on the streets for more than a few hours to get a sense that young Hong Kong people know that they are making history. In the recent “clean-up” thousands of yellow sticky-note messages are souvenired to save them from the garbage collectors.

The digital camera-in-phone is irresistible. Millions of images have created a living archive. The children of the protesters will memorialise the umbrella as an inspired symbol of passive resistance to the abuse of naked power.

From Oxford, I fight a lightweight human rights battle of my own. My near-new suitcase comes off the Heathrow carousel without its handle. The airline refuses to accept responsibility. I protest. They offer a compromise: get it repaired when you get home to Melbourne and they will pay the bill. A man of 76 years, I tell them, cannot lug a suitcase around the globe without benefit of handle. You can do better than that, I tell them. Ashamed, they surrender and pay reparations. If only all the struggles of the world could be resolved so easily.

At Greenwich, our hotel room has an engraved glass bathroom door. From a throne of my own, I can read the headlines: “Revolutions, executions, weddings, beheadings, Kings, Queens, consorts (and bad sorts), jousts, plots…here’s the Greenwich Visitor’s guide to Greenwich’s Royal past.” History while you shower! It was all clean fun in those days. How readily the blood of violent conflict is washed away.

The Imperial War Museum is flourishing in the centenary of the “war to end all wars”. Intending to spend an hour or so, I stay the whole day; and still there’s more to see. Outside, a pair of 100-ton guns with a range of 16 miles compete for attention with a chunk of the Berlin Wall shouting its graffiti slogan “Change your life”.

You pass them after a short walk through the Tibetan Peace Garden opened by the Dalai Lama.

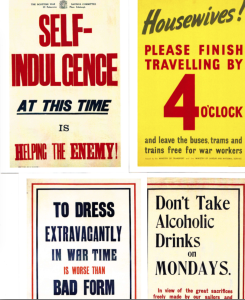

Inside, I view the work of British artists of the war, under the title “Truth and Memory”. In the bookshop they sell other memories – reproductions of wartime posters:

“ARE YOU FOND OF CYCLING? IF SO WHY NOT CYCLE FOR THE KING? RECRUITS WANTED…BAD TEETH NO BAR”

Self-indulgence helps the enemy, Britons are told – emphatically:

At the front, young soldiers are primed on rum – even on Mondays.

At the Tower of London I see a spectacular art installation to commemorate one hundred years since the first full day of Britain’s involvement in the First World War. Entitled Blood Swept Lands and Seas of Red, the installation of 888 246 red ceramic poppies – one for each British fatality in the First World War – fills the moat around the Tower. I am just in time: all the poppies are now sold to the public and the dismantling has begun.

I suppose the millions of pounds shared equally amongst six service charities will be put to good use. While I’m sure that two of the aims – to “create a powerful visual commemoration” and “to reflect the magnitude of such an important centenary” – were achieved, I’m not so sure about the other – to create “a location for personal reflection”.

In Trafalgar Square I am reassured to find officials retain a sense of the ridiculous. Standing tall alongside Nelson and other famous cocks-of-war stands a preposterous cobalt blue chook – with attitude.

I fly to see a friend in Norway. I resist seeing the world war two bunkers again. The majestic monument to the Battle of Hafrsfjord at Gamle is another matter. The three giant swords embedded in rock is surely the most striking memorial I’ve ever seen. I have to take another set of photos to add to those I took on previous visits.

But it’s the unexpected Christmas pageant in the fading light at Sola that I remember best. Scores of children carry flaming torches with happiness in their hearts and carols on their lips.

Eventually I get to Sweden via Copenhagen, Denmark. I can’t pretend to understand the complex relationships between the Nordic nations throughout the centuries, let alone in the twentieth century. I know a little about the German invasion and occupation of Norway and Denmark from 1940. I pick up some discussion about Sweden’s neutrality which, at times, was sorely tested in both directions. I learn about the thousands of refugees, many of them Jewish, who fled to Sweden from Norway and Denmark where they were hospitably received. I wonder if that is entirely true of the refugees of the modern era. If there are tensions, and there surely are, they are carried quietly. [UPDATE: see this news item.]

The conference goes well. The University of Lund is openhearted. Discussions are civil. Controversial argument is met with counter-argument, or a polite request for a fuller version of the paper. Applause is warm but short – each day ends at a bar for more animated but never agitated discussion. Early morning greetings are heartfelt once the coffee arrives.

The only weapons in Lund are the cycles without brakes mounted by half-crazed students late for class and with no regard for elderly pedestrians who must share the same tracks.

By the final afternoon, brain-drained, I beg off to visit the famed Skissernas (Sketches) Museum. I find an incomparable collection of first draft sculptures or early sketches of famous works – not considered to have the same value as their finished product and gifted or sold for a nominal amount. It’s an archive of the creative process, showing the path of the artist from the first idea to the finished work.

I wonder if some equivalent museum would like to acquire my first-draft novel before it becomes a best-seller?

On the way home, the Hong Kong uprising is about to be cleared by the police and military.

The messages are history in the making.

PHOTO CREDITS: Frank Golding & Elizabeth Moore-Golding (2014)

Good day! Wonderful post! Please keep sharing because I will be staying tuned for

more!

I understand your idea, and I completely appreciate your post.

For what its really worth I will tell all my friends about it,

very resourceful.

loved it Frank – thanks for sharing – hope you don’t mind but I’m sharing it further!

Very happy for the share KJ