- THE LARGE INSTITUTIONS

In 1849 the Mayor of Melbourne, approached a charitable organisation, the Dorcas Society, for urgent help with the children of a man who had murdered his wife. A stop-gap was found for these and other urgent cases of destitute and homeless children, the ‘uncriminal orphans and friendless children’. In 1850 the Dorcas Society set up the first informal orphanage in a cottage behind the Royal Oak Hotel in Queen Street.

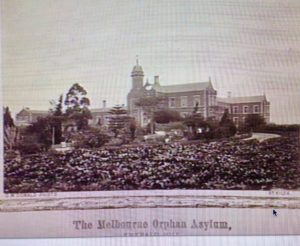

But it soon became obvious that stop-gap measures were not adequate for the numbers of needy children. The St James’ Orphan Asylum and Visiting Society decided in 1851 to set up the Melbourne Orphan Asylum first in the city, then in tents in Kew, and finally in a new building in Emerald Hill (South Melbourne) in 1856.[1]

Meanwhile, an alternative make-shift arrangement was situated not far from where we sit tonight: the Benevolent Asylum at the junction of Curzon and Victoria Streets which opened also in 1851.

Mary Kehoe’s work published in 1998 by the Hotham History Project reveals that, initially, the Asylum served as an omnibus institution: immigrants’ home, blind asylum, lunatic asylum, lying-in hospital, home for the aged and infirm, and orphanage. In 1854, the peak year for children, it housed 87 children, three to a bed with some children sleeping on the floor.[2]

However, it was obvious that the Benevolent Asylum was no fit place for children and the last of them were moved out of North Melbourne to the new Melbourne Orphan Asylum in 1857, and the North Melbourne Asylum focused increasingly on housing the aged poor.[3]

In the decade of the gold rush, the population of the colony soared from around 90,000 to more than half a million. Many mothers and children were left to fend for themselves without support.[4] There was great alarm at the increasing numbers of abandoned, destitute and delinquent children in the colonies—and an air of panic among the gentry.[5]

In this period, the 1850s and 1860s, several other large orphanages were established—a Protestant orphanage in Geelong, and Catholic orphanages in both South Melbourne and Geelong. The Catholics never liked to let the Protestants get their hands on Catholic children. These and others, like the Ballarat Orphanage, where I and other members of my family were inmates, would be part of the warehousing system for more than a century.[6]

The Melbourne Benevolent Asylum and the large orphanages typify a dominant motif of welfare that continued for more than a century. To relieve the state and taxpayers of direct responsibility, Victorian governments provided grants of land and matching funds to churches, groups of philanthropic citizens and charities. They were all equally determined to avoid the Poor Laws of England (and the taxes they entailed) while recognising the need for institutions to house the ‘deserving poor’.

——————————————————————————

[1] Donella Jaggs, Asylum to Action: Family Action 1851-1991, Family Action, Melbourne, 1991.

[2] Kehoe, Mary, The Melbourne Benevolent Asylum: Hotham’s Premier Building, Hotham History Project, Melbourne, 1998, p. 24. It was renamed the Melbourne Benevolent Asylum in 1868 (to differentiate it from other Benevolent Asylums opening in places like Ballarat and Bendigo). The Royal Commission into Charitable Institutions of 1890 deemed it a fire trap and recommended it and its elderly inmates be moved to the countryside, namely Cheltenham. It took until 1911 to make the move, and the Asylum was demolished.

[3] Kehoe, Mary, The Melbourne Benevolent Asylum, 1998, p. 28.

[4] Helen Doxford Harris has compiled some lists of wife and child deserters from Police Gazettes and Police Correspondence Files: http://helendoxfordharris.com.au/historical-indexes/wife-child-deserters

[5] Report No. 3 of the Royal Commission on Penal & Prison Discipline: Industrial & Reformatory Schools, Government Printer, Melbourne, 1872, p. iv, reported: ‘The bulk of the population were for years without fixed homes; families were broken up by dissolute habits, children left destitute by the frequent fatal accidents that occurred at the mines, and the bonds of parental obligation were weakened or ruptured by a roving life and fluctuating fortunes.’

[6] By 1866, there were 894 children in the two Melbourne and three Geelong orphanages: Statistics of the Colony of Victoria for the year 1866, compiled from official records in the Registrar-General’s Office, Part VII, Government Printer, Melbourne, 1867, p. 15.