- ORPHANAGES NECESSARY BUT NOT SUFFICIENT

When Governor Hotham laid the foundation stone for the Melbourne Orphan Asylum in Emerald Hill (South Melbourne) in 1854, he warned that it was not just a matter of supporting the ‘innocent victims of misfortune’, but the citizens of the colony had another political duty. ‘Remember,’ he said,

that these orphans, if not carefully looked after, will shortly go upon the town and become pickpockets. Of the prospects of the female portion, I need say nothing: I leave that to your own understandings.[1]

Hotham’s concern was the child as threat. A strident ‘law and order’ campaign arose in Melbourne and the provincial towns. Newspapers and magistrates led a crusade to rid the streets of ‘urchins, waifs and strays, street Arabs and youthful Bedouins’, rascals who were ‘hastening with a fatal facility into an appalling precocity in vice and crime.’[2]

The fear of street urchins mingled with the urge to rescue children from dysfunctional families who might raise the next generation of thieves and felons. The Ballarat Star castigated the street urchin’s

wicked parents [who] have dropped upon him the black poison-drop of their example of vice and crime...[3]

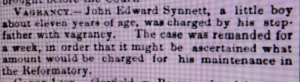

They could have been writing about my great-grandfather Edward Sinnett who was ‘rescued’ from ‘the dark shadows of youthful depravity or destitution’ to be trained to be ‘god-fearing and industrious’.[4] He was 11 years old when he was arrested and charged by his step-father as a neglected child under a new Act of the Victorian Parliament, the Neglected and Criminal Children’s Act of 1864, the first Victorian law governing child welfare in the colony.

The Act set child welfare within a criminal justice framework.[5] And established what would be an enduring policy couplet: the deserving poor (neglected, children or widows or impoverished) and undeserving poor (criminal or children of criminal parents or those with intemperate habits, immorality, alcohol—now we would include drugs).

The law defined a ‘neglected’ child as any child already resident in the Immigrants’ Home, as well as any child found begging, homeless, living in a brothel or with a thief, prostitute, drunkard or convicted vagrant, an offender whom the justices think should be sent to an industrial school rather than gaol or reformatory,[6] and finally, any child declared by their parents as uncontrollable.[7]

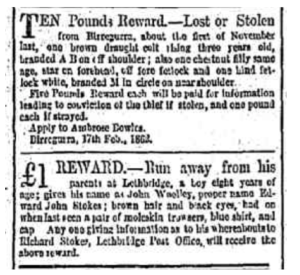

My great grandfather was homeless because he ran away from a violent stepfather, but when his stepfather father offered a reward (less than the reward for horses) and caught up with him, he declared him uncontrollable.[8] \

Had the new Ballarat Orphan Asylum opened in time for my great-grandfather instead of a year late, he may not have been admitted. His parents would have been required to supply Edward’s birth certificate, their marriage certificate showing his father’s name, and a doctor’s certificate attesting that Edward was free of contagious diseases. Parents and guardians who ‘labored under the impression that all Orphans, without regard to legitimacy, morals or respectability’ would be admitted to the Orphan Asylum were badly mistaken because this was an institution ‘for the Orphans of honorable parents in contradistinction to those Institutions established for the reception of the criminal and abandoned.’[9]

The government, however, would have to take all sorts of children, deserving or not. With the Neglected and Criminal Children’s Act 1864, it established a new Department of Industrial and Reformatory Schools. A constable could take a child before a justice, and if he found the child to be neglected, could sentence the child to an Industrial School for between one and seven years. If the child was convicted of an offence he or she could be sent to a reformatory school. In passing, I should hasten to add that there was always—and would continue to be—some blurring of the categories neglected and criminal.

A child found guilty of a criminal offence could also be sent to goal and, when that term ended, then sent to a reformatory. My great-uncle Samuel Sinnett, one of Edward Sinnett’s sons, suffered just that double whammy at around the turn of the century.

You might have imagined a government passing such a law would have industrial and reformatory schools established in readiness, given that in the first year of its operation 1865, police rounded up 868 children (three-quarters of them under the age of ten). By 1866, the Industrial Schools had beds for 1,320 children, 68 percent of them boys.[10]

They were all given numbers—Edward Sinnett was number 707. I know my great grandfather was the 707th because the children were given a registration number in order of admission—and the sequence continued up to 1962. In 1940 I became ward of the State of Victoria number 66852 charged with the same offence of being a neglected child. And institutions were still requiring children to be checked for syphilis and epilepsy. Welfare history is as much about continuity as it is about change.

But back to the Edward’s time, the 1860s: accommodation for children was one continuous crisis.[11] The already overcrowded Immigrants Home near Princes Bridge on the Yarra River was declared the Melbourne Industrial School[12]. There were hundreds more than the facility could accommodate, and, with the police roundups, the numbers grew by the day. When Edward was incarcerated in the Industrial School it was in crisis—a disease-ridden, lice-infested and dangerously over-crowded hellhole. An outbreak of ophthalmia left many children completely blind. Some 117 children died in that hell-hole that year.[13]

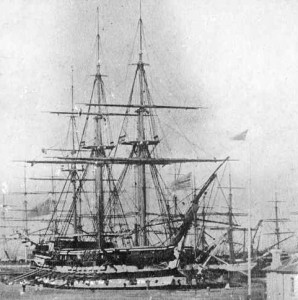

Edward was later shifted to the hastily built Industrial School at Sunbury, but he escaped and was recaptured and transferred to the floating Industrial School, the brig Sir Harry Smith moored off Sandridge. When he absconded a second time he was deemed a criminal child and sent to the Reformatory ship, the Nelson, another hulk moored in Hobson’s Bay. He was released after five years—the fifth year was added to his initial four-year sentence.

Industrial Schools and Reformatories were not a government monopoly. There were church-based ones (like the notorious Bayswater Boys Reformatory run by the ‘Starvation Army’, or the Paradise Reformatory for Catholic boys—which closed when boys continually ran away, from Paradise!)

Other reformatories were run by charities, even a few run by individuals (like Mrs Rowe’s Brookside Reformatory for Girls near Ballarat). Some sites were multi-purpose like the Abbottsford Convent where the Sisters of the Good Shepherd ran both an Industrial School and a Reformatory for Girls as well as an orphanage—all three simultaneously on the one site.

The government has always been happy to contract out children’s welfare services to private enterprise and the non-government sector without too much concern for quality control or accountability[14]—a feature which would eventually become a matter of public shame through the Victorian Parliament’s Betrayal of Trust inquiry and the current Royal Commission on child sexual abuse. But that’s another story.

———————————————————————————

[1] Qu. in Nell Musgrove, The Scars Remain: A long history of Forgotten Australians and children’s institutions, Australian Scholarly, Melbourne, p. 13-14.

[2] Ballarat Star, 5 December 1859: 2.

[3] Joan Brogden, Neglected—or Criminal?: The Sunbury Industrial School, Self-published, Melbourne, 2000, Vol. 3: 29.

[4] Argus, 19/8/1872: 6.

[5] Dorothy Scott & Shurlee Swain, Confronting Cruelty: Historical perspectives on child protection in Australia, 1992, p. 4.

[6] That is a lesser offence or a very young child—although I have found children as young as six in reformatories.

[7] Other States of Australia used similar criteria—and those criteria endured largely unchanged for many decades: see Shurlee Swain, ‘History of Child Protection Legislation’, Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual, Sydney, 2014, Appendix 2.

[8] See Frank Golding, That’s Not My Child: A family at war, forthcoming.

[9] Committee of Management, 2nd Annual Report 1866: 12.

[10] Statistics of the Colony of Victoria for the year 1866, compiled from official records in the Registrar-General’s Office, Part VII, Government Printer, Melbourne, 1867, p. 21.

[11] The Annual Report of the Department of Industrial and Reformatory Schools for 1879, reported that the period before boarding-out was marked by: ‘continuous and wearying efforts to obtain accommodation for the children. Quarantine station, immigrants’ shelter sheds, military barracks, penal hulk, gaol, war ship, and powder magazine being made successively to do duty in sheltering the children; the one characteristic being common to the whole, viz., utter unsuitability.’ Annual Report of the Department of Industrial and Reformatory Schools for 1879, p.3.

[12] Report of the Inspector Industrial Schools, 1867: 3-5; and Argus 13/7/1867: 6

[13] Report of the Inspector Industrial Schools, 1867: 3.

[14] John Poynter in Mary Kehore, The Melbourne Benevolent Asylum, 1998, p. 5.