UPDATE

The ten worst blunders in child welfare in Australia since 1788. COUNT DOWN TO NUMBER 1

It has been hard deciding which of all the many mistakes of the past – and those which continue to be made – warrants the title “the worst”. But here it is.

BLUNDER # 1: Having inflicted significant damage on children in their ‘care, authorities pushed them out with unseemly haste, and failed to see that they needed to put right the damage done and restore the connections to family and community.

After traumatising the children in their ‘care’, welfare authorities turfed them out as soon as they could and promptly washed their hands of all further responsibility.

The authorities have never felt the responsibility that a ‘normal’ parent would feel for their child moving towards independent adulthood. Most ‘normal’ families prepare their young for leaving home and provide a safety net to which young people can return over a considerable period of time after they leave.

Most young people from intact families still live at home till their early 20s, and their parents continue to give them practical, emotional and financial advice and support years after they leave home.

Although some young adults are anxious to leave home as soon as they can, the process usually involves a long transition period during which young adults leave and return home again as needs arise.

By contrast, many a ward of the State will tell you how, as soon as they reached school leaving age, they were sent on their way with a change of clothes, a paper bag or a flimsy brown suitcase, some small change and, if they were lucky, a temporary boarding address and a job. A good parent would never dream of dumping their child in that manner.

Some ‘care’ leavers vividly recall being told in harsh language not to come back…or the tongue lashing from a staff member about how they expected them to be soon in gaol…or working on the streets. There would be no safety net if things went wrong – as they often did.

The vast majority of ‘care’ leavers were poorly educated and unskilled. Many were psychologically traumatised, angry and confused, emotionally vulnerable and ill-prepared for independent living – with no idea about handling money, how to use public transport, how to relate to people of the opposite sex. Some had no experience whatsoever of how a regular family operates.

Many had been brutalised – physically, sexually and emotionally – while in ‘care’ and began life in an unwelcoming adult world as adolescents with a massive chip on their shoulder and a sense of shame about their background. Those who had been sexually abused often felt that they would have to carry their dirty secret with them for the rest of their lives. And many did keep it a secret for decades – and suffered even more for that.

Many did not know if they had family members who were still alive, or if they were, how they might meet up with them.

The Senate Inquiry (2004) reported on health issues:

Evidence was received of general physical, psychological and dental health problems through to severe mental health issues of depression and post traumatic stress disorder. The consequences of lifestyle for many since leaving care such as drug and alcohol addictions, homelessness, unemployment, unsafe sex practices and other destructive behaviours have also had a damaging impact on their health. For some, they carry the legacy of injuries suffered through the abuse they received as a child (6.20).

A recent study by Philip Mendes and others confirms what we know from an abundance of anecdotal evidence that young people in, or leaving, care are disproportionately involved in the youth justice system. And subsequently, having got off to a very bad start, are then caught in a web of unemployment, homelessness and adult prisons. Read more here and here.

What should be expected? A Leaving Care Guarantee

In a nutshell, before leaving ‘care’, all young people should be given every opportunity to acquire the knowledge, skills and resources needed to thrive and survive in the community.

All ‘care’ givers should be obliged to provide a Leaving Care Guarantee under which every young person leaving ‘care’ can expect:

- Support comparable to that given to children who are raised in regular families including the families of child welfare authorities;

- Support in essential matters such as employment, housing, health and education/training should be available up to at least the age of 25;

- If things don’t go well in the years after leaving ‘care’ there will be a system in place to lend a helping hand for as long as it is needed;

- A plan for connecting with kin including access to personal and family records; and, for those who are not able to return to their own family, supported access to community resources who will lend them a kindly hand while they become re-established in the community.

But many ‘care’ leavers need more compensation

Not only should the state provide the care that a good parent would provide for their own offspring leaving home, but it should also try to compensate abused and neglected children for the disadvantages produced by their traumatic ‘care’ experiences.

The state should also actively compensate abused and neglected children for the enduring effects and ongoing disadvantages produced by their traumatic care experiences.

The state and the agencies that held the children are morally bound to assist them to the greatest extent possible. This would include at least the following:

- Free access to counselling and psychological care for survivors of childhood abuse on a life-long basis

- Expedited access to the existing health and mental health care system

- Helping them through access to personal and family records to understand their childhood in ‘care’ and to connect, wherever possible, to their family.

Redressing past wrongs: restorative justice

When introducing a redress scheme for ‘care’ leavers in Tasmania, the then Premier, Jim Bacon, commented:

We cannot change the events of the past but we can demonstrate that we are genuinely sorry and that we are willing to help these people move forwards.

No amount of money will compensate for their abuse as children, but lump sum payments – or ongoing monetary assistance – to survivors of abuse must be paid

- to assist them to recover from the criminal abuse;

- as a symbolic expression of recognition of the enormity of the crime;

- as an expression of the community’s sympathy and condolence for the significant adverse effects experienced or suffered by survivors; and

- to allow survivors to pass the remainder of their years with some degree of physical and mental comfort and to provide their dependants with material benefits as a form of compensation for the difficulties these dependants underwent as a result of the abuse suffered by their parents.

In the light of the failures of the ad hoc redress schemes provided by some States and some churches in the past, a national redress scheme funded by churches, charities and government but administered by an independent statutory authority is required.

Furthermore, those who were abused in ‘care’ should expect to have their allegations referred to police where the alleged perpetrator may still be alive. Prosecutions are still too rare.

In exercising their rights to take civil action against those responsible, legal impediments such as time limitations, impossible requirements to provide documentary accounts and corroborative evidence (in a one-on-one abuse situation) should be eliminated.

♣♣♣

BLUNDER # 2: Authorities failed to supervise and make carers accountable, failed to hear the voices of the children, and were blind to a massive betrayal of trust of vulnerable children

Can there be any clearer example of the Pontius Pilate syndrome that this Victorian Government submission to the Australian Senate Inquiry (2003)?

The system, until the 1950s, was based on the flawed assumption that state wards would be placed in foster care and that charitable children’s homes would only accommodate children placed voluntarily by their parents. As a result, there was no Departmental supervision of these institutions… The inspections that occurred appear to have concentrated on assessment of the physical health of individual state wards, with inspection of the management and standards of care in the children’s homes being of a perfunctory nature.

Were they asleep in the Department for 100 years to not know how their own system worked?

Putting aside the astonishing ‘flawed assumption’ for the moment, it’s a pretty lame excuse to explain away the total lack of supervision of children’s Homes.

After more than 100 years for the Victorian Government set up a system of regular inspection through the Children’s Welfare Act 1954 which required Children’s Homes to be registered with the Department, be approved by the Department, maintain adequate standards of care and be subject to inspection by the Department.

Yet even then, the standards of ‘care’ were not defined in the legislation, there were not enough inspectors to monitor improvements. And no one had time to listen to the children.

Admitting fault comes hard for government and their bureaucrats

It’s even more astonishing to read in the Victorian Government’s 2003 submission that

… If physical or sexual abuse occurred it was a product of the actions of individual staff rather than an institutional phenomenon, although some institutions may have had better procedures for dealing with such issues.

Notice the small word ‘if’? Why?

There is now overwhelming corroborated evidence that physical and sexual abuse did occur, and that it was widespread, and in some cases organised and systemic. What’s more, the Victorian Government knew about it because for years before this mealy-mouthed statement in 2003, it had been paying individual victims and survivors compensation for such abuse to keep them out of the courts.

But it’s reprehensible to try to absolve themselves of all responsibility by claiming that sexual and physical abuse comes down to individual abusers as individuals. Paedophiles were selected, employed and paid by government and non-government organisations alike. Child abusers can only get away with their heinous crimes if their employers fail in their duty of care to the vulnerable children in their ‘care’.

Who Betrayed the Trust?

It should be remembered that many if not all of the children in institutions were in such places precisely because they were allegedly or actually at risk of abuse. To be abused then by the very people into whose safe hands they were delivered is treachery of the worst kind.

The terms of reference of the recent Victorian Parliamentary Committee inquiry the handling of institutionalised sexual abuse pointedly exempted government-run institutions from investigation. The inquiry grilled the churches and charities and the media (rightly) feasted on their culpability, shame and public humiliation, especially of the Roman Catholic Church and the Salvation Army.

However, the essential findings against these organisations apply equally to governments, namely:

- the double betrayal—victims and survivors being disbelieved or paid hush money while offenders were quietly moved on to re-offend;

- the arrant hypocrisy—claims of moral authority while turning a blind eye to clear evidence of crimes against vulnerable children; and

- the lack of accountability—and the wanton refusal to accept any responsibility for the actions of people they employed.

The Betrayal of Trust Report (2013) is a seriously flawed report because of its limited terms of reference. Yet, the Committee did acknowledge as best it could the clear and consistent evidence from a large number of victims, particularly those in the care of the State, that the Government and the police had betrayed them. Read the Report here.

Even when supervision was introduced from the 1950s, there were never enough government inspectors and the monitoring of the government and non-government institutions alike was totally inadequate.

Further, when children did make complaints of abuse they were not taken seriously. They were told they were lying, that they had filthy minds to dream up such stories, and sometimes got a thrashing to add to their troubles. It was the word of a disturbed child against a Priest, Nun, Brother, Superintendent.

Many victims absconded to get away from their vile abusers—at the rate of two a day across the State of Victoria according to CLAN research. But the police often escorted those who escaped back to the institution where the brutality was continued and compounded as reprisal and warning not to report again.

Many of these matters are now under close scrutiny by the Australian Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse. (See Interim Report 2015 here) Although the Commission will work on until 2017, it already can say that

- ninety per cent of perpetrators of sexual abuse were male

- on average, female victims were nine years old and male victims 10 years old when the abuse started

- on average it took victims 22 years to disclose the abuse, men longer than women.

The last point indicates that there is a massive power imbalance between victim and perpetrator that means it takes many years for people to be in a position to come forward – and in the meantime, how they suffered carrying the awful secret every single day.

As they say, a damaged childhood makes for a damaged adult. But it’s not too late to care and to do something to make good the harms caused by the terrible crimes that were perpetrated.

And to make sure it never happens again.

Every child who cannot live with their own family for whatever reason should be looked after in the same way that loving parents care for their children.

♣♣♣

BLUNDER # 3: Authorities lacked respect for the children in their ‘care’, believed that they had limited abilities, and deserved no better destiny than unskilled and gender-based occupations

Child welfare authorities have never shown much respect for the parents whose children were taken into ‘care’. So it’s not surprising that they thought their offspring were never going to amount to much.

Meagre educational opportunity

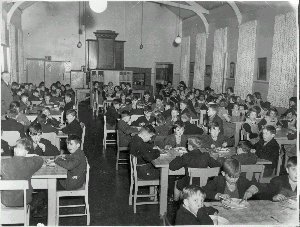

Despite the fact that schooling was compulsory in Victoria from 1872, not all children in out-of-home ‘care’ were sent to school. Where schooling was offered, it was no more than basic training for narrow-defined working-class occupations.

A journalist inspecting the Ballarat Orphanage in the 1880s seemed well-pleased to find children being prepared for their gender roles in life.

The girls are taught and practised in all that pertains to laborious house-wifery. They have to wash, cook, scrub, mend and make clothes, and at the age of fourteen or fifteen, turn out as useful little domestic help as the Australian house-keeper could desire.

But there is more interest perhaps, at least to the masculine mind, in the education of the boys…It begins with good feeding and discipline. It proceeds to the ordinary state school education, but it goes on thence to teaching in gardening and farming, in various trades – indeed to the laying the foundations of a sound manhood in the boy. (Argus, 1889)

By and large, the authorities considered most institutionalised children intellectually inferior. And in the 1920s, they could call on the eugenics movement for ‘scientific’ confirmation.

In 1927, the Victorian Department’s Annual Report saw fit to include a research paper by Dr Cunningham (who would later become the first Executive Officer of the prestigious Australian Council for Educational Research). Cunningham tested the IQs of the children incarcerated at the Depot (Reception Centre) and claimed that they fell into four clear groups, with the proportions being:

- Normal – 19%

- Dull or border-line – 46% (“Often called the moron group…Can be educated within limits, e.g., often learn to read”)

- Imbecile – 33% (“Formal education out of the question.”)

- Idiot – 2%.

On the basis of his findings, Cunningham advised the Children’s Welfare Department to keep a large proportion of the inmates in institutions permanently.

Although it is only a matter of guesswork, it may be estimated that of all children under the care of the Department 40 per cent are cases for whom it would be advisable to provide care and training either permanently or for a number of years. The majority of these would be cases calling for permanent care.

Nobody thought to challenge Cunningham’s testing and classification methods – which would be laughed at today. No one suggested that troubled children ripped away from their parents and thrown into an alienating environment might be too distressed or traumatised to show their true capabilities.

Even as late as the 1960s researchers were claiming:

It is usually discovered that children in institutions are educationally retarded at the point of entry (Tierney, 1963).

And yet people outside the welfare sector could see the merit of providing a broader education.

For example, in 1946 the Victorian Education Department advised the Ballarat Orphanage that the children “should go and mix with other pupils in the suitable post primary schools of Ballarat”. No, replied the Head Teacher, none of the 18 children in Grade 6 would go on to secondary school. Why?

- First, because of the “extra responsibility” involved (Could that mean the risks of letting children out of their sights were too great?); and

- Second, because of “the prior history of the children” (Did he mean that Orphanage kids were not capable of benefiting from education, or didn’t deserve it?

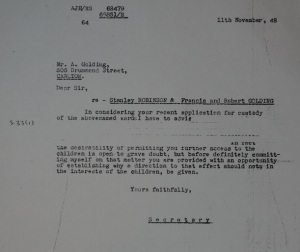

Years later, four children from the Ballarat Orphanage, including me, were allowed to go to the High School at the other end of town. But, the limits were soon questioned. Should I be allowed to finish Year 10? In my Departmental file I found this note:

Undoubtedly, all the boys will return to the mother and Golding in due course and it is just a question of whether he should be retained and given an education at the expense of the State when his future earnings will probably be collected by the mother.

This moral giant of “the welfare” was blind to any benefits that education might bring to me. I don’t imagine he thought of the education of his own children in the same way.

Moral inferiority

Not only were institutionalised children intellectually deficient, they were also morally suspect – especially when it came to matters of sexual behaviour.

In 1923 the adolescent girls placed in a reformatory were described as “leading a depraved life” and “leading an immoral life”. In the same year, an inspection of a boys’ reformatory attributed the poor physical strength of some of the boys to masturbation, and assured the Department that “a close watch is kept…with the purpose of checking the evil, and punishment is administered to offenders when detected.” (Victorian Government submission to Senate Inquiry, 2003, 2004).

In some cases, teachers and staff expected very little of the children. Only occasionally did a teacher express greater ambition for their children, sometimes spiced with a touch of scorn. I remember one teacher snapping:

Little guttersnipes, you are, but I’m going to make you into little ladies and gentlemen if it’s the last thing I do.

Staff could humiliate, abuse and otherwise debase the children in their ‘care’ with impunity. No one cared because the children were not considered ‘normal’ and theirs was the voice without power.

Human guinea pigs

Such was the contempt in which institutionalised children and their families were held that babies and children were used as subjects for medical experiments in Victoria up until 1970 or even later.

New vaccines for herpes, polio, whooping cough and influenza were trialled and hormones from dead people were used to treat short stature. Some of the vaccines had failed to pass safety tests with animals.

In some cases the children developed serious reactions, including abscesses and vomiting. Some former residents believe that they still suffer from the long-term effects of these trials.

Scientists from the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute and the Commonwealth Serum Laboratory (CSL – then owned by the Australian Government) were given ready access to these babies and children without the knowledge or consent of their parents.

A series of articles in The Age in 1997 first drew public attention to this matter. It A that time, the Department of Human Services reported that

it is likely that the research institutes gained consent to conduct the research from staff responsible for the institutions and, possibly in one case, from a Departmental employee.

Parents were presumably considered to have relinquished their rights to be informed or to be asked for consent.

There is no evidence to show that Departmental officers or institutional staff allowed their own children to be used as human guinea pigs.

Several reports in reputable publications such as the Medical Journal Of Australia give details of these experiments. And public comments of regret have been made by scientists involved (Melbourne University went so far as to issue a public apology in 2009 for the part its medical researchers played in these experiments).

Yet when offering its submission to the Senate Inquiry in 2003, the Victorian Government could not bring itself to admit anything, but referred only to

media claims that state wards had been the subject of potentially harmful medical trials in the 1950s and 1960s.

Media claims?

Government capacity for self-delusion is unbounded. Why do I have no respect for their weasel words?

♣♣♣

BLUNDER # 4: Authorities failed to keep adequate records of the children in their ‘care’ and continue to misunderstand the importance of records into the future

When Freedom of Information (FOI) laws were passed in the 1980s, and Privacy laws a little later, word slowly spread that personal historical records of a child’s time in ‘care’ were available. Then a spate of formal inquiries, apologies and rudimentary redress schemes caused a rush of requests.

Many survivors, carrying the scars from their damaged childhood, want to understand why they were in ‘care’ as children, to find out what had happened to their families all those years ago and, hopefully, to connect with whoever remained.

Survivors hoped their childhood records would help them reach back into a strange past where birthdays, anniversaries, christenings and other family occasions were never celebrated. A past where personal identity was formed without photo albums, memorabilia, and family stories handed down by parents and other relatives.

However, many survivors have since been told that their files were destroyed or can not be located. In 2012, the Victorian Ombudsman found gross negligence in the Department’s indexing, storage and physical preservation of thousands of records, some potentially crucial to criminal proceedings.

Vital documents were ‘lost in the system’. When pressed, the Department, occasionally, discovered they held them all along (Auditor-General 2012). Yet, hundreds of clients – among them survivors who were raped and sexually assaulted as children – have been unable to access any documents of their time in ‘care’.

This story goes back a long way

In the 1960s, researching the Victorian Children’s Welfare Department records, Len Tierney from the University of Melbourne reported that ‘Few institutions had anything which could be considered a case-record.’ Some Homes kept no records whatsoever. Head Office laid down no requirements.

When a child was sent to a Home, very little information was sent with them:

… a brief history of the child was sent to the Superintendent of the institution. This history was no more than a précis of the Police complaint, a statement of the court decision, and an itemised account of the disposal of the other children in the family. There the child would remain, and for practical purposes the file was closed, until it became necessary to remove him from the institution.

Tierney reported that

Often superintendents lacked a knowledge of even elementary vital statistics: the age and occupations of parents, the numbers of siblings, the addresses of key relatives, and so on.

In one case at the Ballarat Orphanage, a child died and her grandmother was listed on the death certificate as the mother despite the Orphanage having written confirmation of the relationship.

Transfers of children often did not require accompanying records. Siblings were placed in different institutions and over time it was common for that kinship relationship to be ignored and forgotten.

Meanwhile at Head Office, Tierney found that there was

- no central register of all children in substitute care in Victoria;

- ‘no simple method of discovering where children were located’;

- no simple way of knowing how many children were in care.

Some 20 years later, the Norgard Inquiry (1976) informed the government that

the Department’s present provisions for record-keeping and reviewing progress of its wards requires thorough overhaul. Inefficiency in these fields can result in real – sometimes permanent – harm to individuals.

Yet, nothing changed.

In the 1990s, the Department’s most senior officer, Dr John Patterson, complained that his Department was still not tracking clients from one service to another or through changes of addresses and change of names. Patterson described the existing system as ‘pitiful’.

When the Senate Committee (2004) asked for simple statistics on the number of children who were wards of the State of Victoria, the Department was only able to give a guesstimate because figures were ‘estimates based on incomplete data’.

Also, some children may be double counted, through being received into care more than once…For the period 1928 to 1949 there is no reliable data on annual admissions to wardship as Victorian government departments stopped publishing annual reports during the Depression as an economy measure.

The Department had no records of the numbers of children admitted to Homes by their parents or other family members who then went on to become wards of the State.

Despite all the above, thousands of personal records were kept and filed away in archives, and have now been accessed. It is now crystal clear that the writers of these records about children never had any expectation that the children they were writing about would one day come as adults to read what was recorded about them and their families.

What’s in the files?

Those who have gained access were often disappointed, frustrated, and angry with what passed as the story of their childhood.

Grossly offensive, moralistic judgements comments caused great pain and distress.

The trauma is revisited when intelligent adults read that they were assessed as ‘high grade mental defective’. Many find the dossiers reveal more about the writers’ prejudices – gratuitous personal insults and spiteful comments. Many also hotly contest the interpretations of events which have remained unchallenged down the decades.

Many report that their records are full of misspelled or incorrect names, incorrect dates of birth and more fundamental misinformation. One Care Leavers reports that:

There was unopened mail in my file and I was shocked that it was from my family. It was withheld for 60 years.

That is by no means a unique example.

Yet, there were also some positive discoveries. Adults now in advanced years discovered in their files that their parents asked repeatedly to have them returned. As children, they were never told about life-shaping decisions, and it would be decades before they understood.

By contrast, vital medical histories and school reports are missing. Some survivors hoped for photographs of themselves or family members. These are a rarity.

The process

There is also great confusion about how people exercise their right to their personal records, especially when they were a client of both the Department and one or more non-government agencies – as many were.

The Department continues to direct former residents seeking personal records to apply to past providers. In many cases, people who were raped or sexually assaulted are required to return to the place where they were violated to seek their personal records.

Censorship

A common concern is the knee-jerk censorship of information about ‘third parties’ mentioned in personal files. The third party is often a parent or a sibling, and the information that is withheld is a crucial part of their family story. Some applicants want their records precisely to gain information about the identity of ‘carers’ who were also sometimes their abusers.

One other remarkable finding about these historic records: search high and low, you will not find the voice of the child anywhere in them. The files are strictly bureaucratic. Their purpose was to encode a version of reality constructed by ‘care’ givers that served to justify the actions they took.

The narrative of the survivors is, of necessity, a matter of restoring to them their voices – an ongoing task that will challenge the bureaucratic narrative found in the archives.

♣♣♣

BLUNDER # 5: The welfare system was based on lies and deceit, and the public has been kept ignorant of what was going on – until very recently.

The Australian system of child welfare has been constructed on systemic lies and deceit. Sometimes, this is framed as being in the interests of the child. Here’s a clear example relating to the adoption of children.

Every care…must be exercised to keep them [adopted children] happy in their ignorance as the disillusionment would assuredly…make the rest of their lives unhappy to learn they, in most cases, came into the World nameless and were deserted by those responsible for their existence (Children’s Welfare & Reformatory Schools Department, Annual Report 1934).

‘Happy in their ignorance’?

Many a person who grew up in ‘care’ was told told that their parents did not want them but decades later found unopened letters from their parents in their files. Others were told that their parents were dead only to find out later (often too late for reunion) that this was not true. Others had their names changed and it was not until advanced adulthood that they found that as infants they had been separated from siblings who carried different names.

It was not just the children who were lied to. In his Annual Report to Parliament of Victoria for 1934, the Secretary of Children’s Welfare Department and Reformatory Schools, was very pleased to report that children in institutions were

- ‘treated kindly, patiently, and given sympathy and skillful treatment’

- ‘wonderfully cared for by a fine body of men and women’,

The Secretary was adding to a long tradition created by earlier Departmental Heads – and the media were perfectly happy to relay the good news. Authorities told the parliament and the public what they wanted them to hear about how children were treated, and the media were happy to oblige.

Individual institutions harnessed this uncritical goodwill in their on-going appeals for public support. To take one example: the Ballarat Orphanage was always willing to put on a good show for the media. Visitors were easily deceived. One reporter was so impressed with the food he saw served to the children that he was moved to issue a jovial warning:

The dinner in the Orphanage at Ballarat would shock any member of a board of guardians of the old world. He would declare that if that sort of thing was tolerated, men would begin to commit suicide to make orphans of their children (Argus, 8 June 1889).

When the visitors were gone, the inmates reverted to the customary food, which – like the reporter’s joke – was in very poor taste.

Not that the children’s opinions were ever asked for. Newspapers hundreds of miles away were more than happy to repeat a feel good story:

Mr. Arthur Kenny, the Superintendent of the Ballarat Orphan Asylum, turns out a number of lads each year so thoroughly capable that they have earned a high reputation in many parts of Victoria. For every lad old enough to leave the institution there are 10 to 20 applications, and the Melbourne ‘Argus’ states that there would be no difficulty in obtaining places for 10 times the number the Orphanage farm can supply (Sydney Morning Herald, 6 October 1904).

Was it any wonder that landowners across the country clamoured to be given another pair of competent hands at dirt-cheap rates. And the boys, isolated and powerless, had no champion to spread the world that they were worked to the bone, for little or no pay, and treated little better than the farmers’ dogs out in the sheds.

It was much the same for the girls, who were valued as cheap housemaids, cooks, cleaners and sometimes the defenceless instruments for the pleasures of the men of the house, and their sons.

It would have come as a great surprise to the inmates that after a visit to the Ballarat Orphanage in 1929, the incongruously named Inspector of Charities, Mr Love, described it as “the finest composite children’s institution that he had seen in the world” (Argus 19 June 1929).

It was not only visitors to the institution who were deceived. The volunteer members of Management Committees were usually too busy with their own everyday affairs to pay close attention to the day-to-day running of the institution. Self-righteously they approved rules and regulations like:

No employee will be allowed to punish any of the children under any pretence whatever. Any of the children making any impertinent remarks to or about any of the employees shall be immediately reported to the Officer in Charge (Rules for Employees issued by Superintendent 1885).

They were in no position to know that such rules were blatantly flouted every day. It would take more than a century before former inmates had the collective strength to blow the whistle and find a media receptive to their experience – and headlines like this shocked the public:

- “Violence at the Ballarat orphanage was institutionalised” (The Age, 21/7/2001).

- “Terror Haunts Victim” (Ballarat Courier 28/10/2002)

It must have come as a great shock for the citizens who had given so generously over the years to see headlines like those. After all, they had been fed fairy-tales like: ‘In many respects [institutions] were equivalent to up-to-date boarding schools’ (Annual Report to Parliament of Victoria for 1934, the Secretary of Children’s Welfare Department and Reformatory Schools)

The public would not have known that so many inmates absconded from these Homes that it was necessary for the authorities to present the police with a regular list to be published in the Police Gazette every fortnight – for police eyes only. Across Victoria in an 18-year period, according to CLAN research, more than 3000 absconders were reported and their arrest sought. That’s one every second day.

And not all absconders were reported in the VPG: many, perhaps most, were captured and returned before a notice could be published (CLAN evidence presented to Victorian Parliamentary Committee of inquiry, 17/12/2012). These ‘wonderfully cared for’ children were making their feelings known as best they could – with their feet. When they were arrested no one thought to ask them the obvious question why they were fleeing. The police just took them back to the Home to cope as best they could.

It would take a Senate Committee in 2004 to gather and publish the evidence that gave clues as to why so many ran away from such hellholes. The Senate Committee heard what amounted to

a litany of emotional, physical and sexual abuse, and often criminal physical and sexual assault…neglect, humiliation and deprivation of food, education and healthcare…widespread across institutions, across States and across the government, religious and other care providers. (Senate of Australia 2004: xv).

A decade on, the Australian public been further shocked at the scale and magnitude of the sexual abuse revealed almost daily by the Royal Commission.

The weight of testimony from survivors and victims has finally shown that the welfare system has, through a continuous mass deception, covered up a shameful chapter in Australian history.

♣♣♣

BLUNDER # 6: Parsimony has always ruled – ‘care’ provided on the smell of an oily rag.

Convicts weren’t all that was transported from ‘the mother country’. Attitudes about spending on the poor were shipped out too. Hard-working and thrifty citizens should not have to bear the burden of the children of the poor. Poor relief only encourages depravity and wantonness, etc. etc.

While accepting concerns about the criminal classes and abandoned children, governments have always loathed spending too much taxpayers’ money on looking after them.

In part, this reflects an entrenched belief transported from Great Britain that it’s the role of churches and charities to care for children in crisis. From there, it’s always been a bit of a tussle between government and churches as to who ‘owns’ the problem and who should pay.

Governments were happy enough to make land grants to enable the child warehouses to be built by churches and charities and never held back in populating the orphanages with wards of state. But they were never willing to provide for the adequate operation of those institutions. It’s little wonder that the Annual Reports of these institutions were fixated on financial shortages and fund-raising appeals.

Children were used as unpaid labour – in laundries, mending and even making the clothes and boots, tending the vegetable gardens and the dairy herd, ploughing the paddocks and even building the premises. Although it was rationalised in public as training for the future of these poor ‘waifs and strays’, what went on behind the high walls was little more than slave labour.

From time to time over the decades, mouthing the language of individual ‘care’, authorities preferred boarding out (placing the child with a foster family) to the large child warehouses, but they were mean-spirited when it came to paying foster families for the real costs of caring for a child. And still are to this day.

The current-day crisis in foster care – families have stopped putting up their hands – is nothing more than the inevitable outcome of governments being unwilling to put their money where their mouths are.

Even within the now discredited residential care system, children are exposed to systematic and routine sexual abuse and exploitation because the government will not provide adequate funding for trained supervisory staff (see The Age 13 March 2014 here).

Leaving aside legal adoption where the full costs are willingly offset by financially-viable families, the cheapest option, and in the long term the most likely to lead to all-round happiness, is reunification with the child’s family. In many cases, this requires intensive support to help overcome the difficulties that lead to family breakdown in the first place.

Such support requires intensive funding in the short term – and this frightens governments who haven’t the vision to imagine a social (let alone an economic) return on their investment.

The future costs of short-term political blindness will never be addressed because these costs extend well beyond the election cycle and children in ‘care’ are not – and never have been – a priority.

Care leavers will continue to be heavily overrepresented

- in the mental and physical health systems,

- in prisons,

- in the queues of the chronically unemployed and homeless,

- not to mention intergenerational institutionalisation

♣♣♣

BLUNDER # 7. Children were too quickly separated from their family for short-term gain with little regard for the long-term pain.

Moral contagion was considered as much a threat as smallpox in Australia’s colonial days, although those with the power could please themselves as to how to define morality.

The first known removal of a child in Australia occurred in 1789. When Mary Fowles was aged about five, Governor Arthur Phillip sent her to Norfolk Island as ‘an act of philanthropic abduction’. No doubt Phillip thought he was acting in Mary’s best interests in saving her from from her convict mother, described as ‘a woman of abandoned character’ (Robert Holden, Orphans of History: The Forgotten Children of the First Fleet).

Five years later, Mary was assigned to the service of Thomas Jamison, the Assistant Surgeon. It may have been a sign of things to come in Australia at large that Jamison, ‘out-of-sight-out of-mind’, lived openly with a convict mistress, Elizabeth Colley, with whom he had a brood of illegitimate children while making a fortune trading in alcohol and other goods in open defiance of Governor Bligh.

Nothing is known about Mary’s life in the Jamison/Colley household or about her ultimate fate. And there appears to be no record of Mary’s mother and no hard evidence that mother and daughter were ever reconnected.

While the fear of smallpox has greatly diminished over the years (thanks in part to Jamison’s pioneering with smallpox vaccinations), the same cannot be said for the fear that children would catch immoral habits – or other undesirable characteristics – from their parents.

The tragic story of the Stolen Generations is now so well-known as not to need elaboration here. But hundreds of thousands of non-Indigenous Australian children were separated from their families, in many cases as a first resort. And the practice continues.

Once taken, many of the children were not allowed to see their parents again. Some were told their parents did not want them. Others were told their parents had died (only to find out in later life this was a lie). Letters from family were opened and the contents vetted, or filed unopened.

Siblings were often separated for the convenience of administrators:

Families would be split with children sent to different institutions. Many would not see their parents again and with minimal or no effort made to keep siblings informed of each others whereabouts, let alone arrange meetings, families inevitably drifted apart, often permanently (Senate, Forgotten Australians, 2004, 4.53).

“Our entire family was ripped apart and we can never get back together. They split me away from my 1-week-old brother and we never knew each other until we were old. I had cousins in St. Aidans and the nuns never told me. I never knew my family. How can you get back together when you don’t know each other?” (Submission 264, p. 4)

Is it any wonder that many children in ‘care’ felt abandoned, bewildered, resentful and angry? And remained so for much of their adult life?

Appearing before the Senate inquiry, one former institutionalised child put it this way:

“You cannot give me back my childhood and you cannot give me back my parents, and just saying sorry does not quite cut it” (Senate Forgotten Australians, 2004, 7.93).

♣♣♣

BLUNDER # 8. Authorities prefer to apportion personal blame rather than identify and remedy the real causes of family breakdown.

Two types of people populated Menzies’ world in 1940s Australia: the industrious who succeeded and the shirkers who failed. The merits and sins of the fathers were personal attributes, and they inexorably passed on to their sons (decent mothers didn’t work, and daughters were simply waiting for Mr Right).

Fast forward to 2014: Abbott and Hockey continue to espouse the simple equation: Intelligence Plus Hard Work Brings Success. Life chances are captured in three-word slogans:

- Lifters and Leaners.

- It’s Their Choice!

- Hope, Reward, Opportunity.

- Stop the Waste.

In the land of the so-called fair go, there’s plenty of work out there if only THEY would get off their backsides and have a go, like US.

We just can’t stop people from being homeless if that’s their choice. (Tony Abbott, 11/2/2010).

Material worth meshes with moral worth until ultimately nobody can see the difference. Which is fine if you can find, and hold on to, a job – or keep your head above water after the death, desertion or divorce of a breadwinner.

Over many decades, Child Welfare Departments reported annually on the reasons children came into their ‘care’. Departmental heavies constructed charts dividing mothers and fathers into those of ‘good’, ‘poor’ and ‘doubtful’ character. And most of these judgments were made on the flimsiest of evidence – often police reports designed, before the fact, to prove a suspicion about what the authorities called ‘the utterly helpless class’.

In a snapshot of the Victorian child welfare system, Tierney (1963) reports that nearly two-thirds of all children placed in institutions in Victoria are admitted because they are ‘in need of care and protection’. The ‘blame’ falls on ‘inept’ parents who leave their children home alone, ‘malnourished, poorly clad, lacking medical attention and absent from school’.

There is precious little analysis of what that means. Poverty is barely mentioned. There’s scarcely a word about unemployment, or homelessness, or ill-health, or war, or family separation or divorce. Not a hint of lack of support for single parents. No understanding that the capacity to care for children can come under extreme stress when parents face such unbearable pressures and insecurity.

Nobody joins the dots between widespread family breakdown, economic inequality and social class. It’s easier to blame the victims, emphasise their faults and punish their children.

♣♣♣

BLUNDER # 9: Children were placed in institutions on the basis that they were either ‘neglected’ or ‘criminal’; and, to make matters worse, the categories were confused

It’s not hard to find illustrations in colonial times:

- Governor King 1803: Finding the greater part of the children in this colony so much abandoned to every kind of wretchedness and vice, I perceived the absolute necessity of something being attempted to withdraw them from the vicious examples of their abandoned parents.

- Governor Hotham, 1855: Remember that these orphans, if not carefully looked after, will shortly go upon the town and become pickpockets. Of the prospects of the female portion, I need say nothing: I leave that to your own understandings.

Neglected & Criminal Children laws became common across Australia between 1863 and 1874. These usually resulted in the setting up of:

- Industrial Schools for neglected children and

- Reformatories for criminal children.

The preamble to the Neglected & Criminal Act 1864 (Vic) shows the conflation between ‘care’ and ‘custody’

WHEREAS it is expedient to provide for the care and custody of ‘neglected’ and ‘convicted’ children, and to prevent the commission of crime by young persons…

Who was a Neglected Child?

The Victorian Act said any child already in the Immigrants’ Home (which became an Industrial School) plus:

- Beggars

- Homeless

- Children who associated with prostitutes, thieves, drunkards or vagrants

- Those convicted of a lesser offence than a ‘criminal’ child

- Any child whose parents deemed they were not able to control that child but were willing to pay maintenance to the Industrial School.

These criteria established in 1864 carried through virtually unchanged for more than a century.

Who was a ‘criminal’ child?

Any child ‘convicted of any offence punishable by law’. Such a child was to be sent to a reformatory when their gaol sentence expired.

Over time, the system blurred these categories in a number of ways:

- Often it was the consequence of a simple administrative imperative related to the available accommodation and children of both categories rubbed shoulders.

- Often ‘unworthy’ parents were seen as enemies of society and their children carried guilt by association. Len Tierney wrote in 1963: ‘Because the original police evidence was designed to show the failings of parents it is difficult for departmental officers not to prejudge the parents in all respects…Police reports tend to strip parents naked showing them in their very worst character.’

- The language used throughout the system right up to the latter part of the 20th century betrayed the pervasive culture. Neglected children were reported as being ‘detected’ and the ‘offenders arrested’. And the children were ‘charged’, put ‘on probation’ and ‘discharged’.

Further, within many institutions, neglected children were treated like criminals. Isolation cells, harsh corporal punishment, bells and sirens, being called by numbers, marching and military-style drills reinforced the feeling that they were worthless.

It’s little wonder that so many ‘neglected’ children absconded – and little wonder that the authorities routinely supplied a list of absconders to be published in the Police Gazette.

♣♣♣

BLUNDER # 10 : The powerful US divide THEM into the ‘deserving’ and the ‘undeserving’ poor.

At times the powerful fear the poor. At times they show their contempt for them. At times they pity them. The powerful make moral judgments about whether those who are doing it tough deserve to be supported, or whether they’ve brought their ill-fortune upon themselves.

A classic example from a man who would be Australia’s longest-serving Prime Minister, Sir Robert Menzies writing in 1942:

That each of us should have his chance is and must be the great objective of political and social policy. But to say that the industrious and intelligent son [sic] of self-sacrificing and saving and forward-looking parents has the same social deserts and even material needs as the dull offspring of stupid and improvident parents is absurd. (‘The Forgotten People’, Radio broadcasts written and presented by The Rt Hon. R.G. MENZIES. Read the full speech here.)

Fast forward to a different Prime Minister, Tony Abbott, although he was a mere parliamentary secretary to the Minister for Employment, Education, Training and Youth Affairs in 1996 at the time when Sally White met him when she was working at the Commonwealth Employment Service in Preston, at what was called a “Youth Access Centre” where young people came to look for work.

Mr Abbott came up and, in a friendly, hushed conspiratorial tone, said: “Tell me, how do you cope with all these young people with their earrings in their nose and green hair, and get them a job?”

I had just spent a long time with a young girl who had earnestly been coming in regularly to look for work. She was struggling with a lot of issues but was still trying. As she was fresh on my mind, I answered: “Actually, I just had a girl come in who has been looking for…” but I only got a few words out when Mr Abbott abruptly turned his back and walked away while I was mid-sentence. Read more.

Decades on, politicians, media shock-jocks and policy makers still demonise and abuse those who fall on hard times while reinforcing the good fortune of those ‘deserve it’.

6 thoughts on “10 Blunders in Child Welfare”

Comments are closed.

Good history Frank. I would like to have seen a discussion on parents forced to stay in abusive relationships/marriages because of lack of financial support. The introduction of single patent benefit and the difference this made to those caught up in difficult relationships manly women. This also led to fewer children being removed , fewer children going into institutions.

Frank did this period also lead to a higher need for Foster Care, hence the need also to increase the number of Carers. The ongoing struggle to recruit and train and keep potential Foster Parents .

Thanks Phyllis. You’re right: many, many mothers were forced to stay in abusive relationships because of financial necessity. Some also stayed because they wanted their children to have a father (even if he was a s***t). I don’t know how some women managed to survive!

The introduction of family benefits (preceded by earlier, lesser payments) almost certainly helped sole mothers cope a little better. But benefits are never adequate.

The foster care system has a long, history in Australia (and in the UK) especially in South Australia. It was actually cheaper than running institutions and the two systems (institutions and foster care or ‘boarding out’) ran in parallel – even in competition, each with their own advocates. But public policy seemed to be ambivalent and inconsistent – and again government payments never kept up the rising cost of raising a child.

Foster ‘care’ was kicked along again in the second part of the 20th century when authorities began to close the big orphanages and child warehouses. More children today are in foster ‘care’ situations than any other form of ‘out-of-home-care’ – by a long way.

But as you know, penny-pinching and lack of training and other support for carers has blighted the system, in the past and still today. As well, the selection of foster families has had more than a few problems and countless fostered children have had a shocking upbringing with cruel and abusive foster parents.

Nell Musgrove’s research project into foster care in Australia will be – surprisingly – the first of its kind in Australia.

Good points Cherie. I’ll make a considered response in a later post.

Over time, successive governments have failed to make adequate funding of out-of-home care for children that need this, a priority. Hence out-of-home options care are woefully under funded, meaning that resources are scarce and outcomes accordingly, far from optimal.

Although out-of-home care is a measure of last resort, with all other options (including kith and kin placements) typically explored first, there will always be a proportion of children, for whom out-of-home care is the only option. Lack of adequate funding for these arrangements, be they foster care, residential care, or highly specialised therapeutic placements, is a mistake that is paid for over and over again, ultimately by the children themselves as well as society as a whole in terms of the cost of deleterious adult outcomes.

Early intervention is also important, and helps to some extent to prevent children from entering the out-of-home care system in the first place, so money spent at the other end of service system is indeed well spent. That said though, governments ought not abandon children at the pointy end of the sytem, by failing to adequate fund services for the care of those children for whom early intervention is not adequate to prevent them from ending up in out-of-home care.

Without adequate funding to provide the level of care and specialised services for children in out-of-home care that is needed, we condemn these children as a group to far from optimal outcomes. This could be prevented, if only successive governments were astute enough to realise the importance of making funding for out-of-home care options and associated services, a priority.

Cherie, you will see I address some of the points you made so well in today’s post and then there is more discussion relevant to your comments in the exchange between Phyllis and me (above).

A question: Does the lack of funding for children in need reflect government and public apathy or is there something intrinsically punitive in Australian political culture when it comes to dealing with working-class families doing it tough?

Lack of adequate funding, in my opinion, reflects the fact that very few, outside of those directly affected and people employed in the sector, are aware of these issues. Hence, funding for children in out-of-home care is not seen as a priority by either the community, or some governments, because this area of social policy is “invisible” (or non-existent) in the mind of the general public.

From a political perspective, it is also not an issue that is perceived as likely to win as many votes for an MP standing for election, as more mainstream issues might, such as concern for the environment etc.

Most people are totally unaware as to how serious these issues are in terms of deleterious or disadvantaged life outcomes as adults, for the children affected (and in turn, often their children also). Whilst such outcomes are not so for everyone, the evidence is very clear; a disproportionate number of people from this background experience disability, homelessness, and educational deficits in later life. It is my contention that it is more cost effective to prevent these outcomes by properly funding the out-of-home care system in the first place, than it is to try to fix more serious problems at the other end (although a blend of both approaches is required).

There is also a stigma associated with being raised in out-of-home care and many, not knowing better wonder, “what did the child do wrong to be removed from their family?” Of course, the fact is that in the vast majority of cases, the child did absolutely nothing wrong and rather they were removed from home because their families, for various reasons, were unable to provide them with a safe and secure home.

Add to this the (somewhat flawed) notion that Australia is a “lucky country” where “anyone can succeed if they just work hard enough”, and you have your answer. How does this concept work for indigenous Australians? For many not too well and this is not because indigenous Australians are lazy! Rather, it is because, on average, as a group they face additional barriers to education and have poor access to health services. Many (although not all) children and adults with an out-of-home care history are in a somewhat similar position. Australia is indeed a country of great opportunity, but those opportunities are limited for those that face substantial obstacles to the workforce including a lack of education or vocational training, and lack of housing due to being unable to return to the “family home” in times of need during young fledgling adulthood especially.

This is a very complex problem and there is no quick fix or silver bullet that will solve it. What is needed though, to start with, is adequate funding for the out-of-home care sector so that such children can access the specialised help they need to come to terms with the experience of having been removed from their families and in order to emerge better equipped to cope with the demands of the adult world at the other end of their out-of-home care journey.