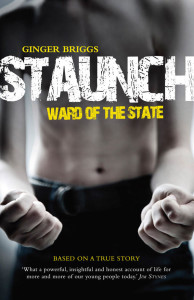

Is fact stranger than fiction? Comments on Ginger Briggs, Staunch, Affirm Press, Melbourne, 2012.

I was so stirred up by this disturbing book that instead of placing it with my regular short reviews of books (here) I wanted to make a closer examination of this fascinating work.

On face value, Staunch is a novel, based on a true story. But Ginger Briggs calls it ” a work of non-fiction about real people”. She writes, “Everything that happens to Andy in Staunch happened to the real Andy”.

We learn that Andy was ‘relinquished’ at birth, and was ‘divorced’ from his adoptive parents at 10. His father was a violent drunk, his adoptive mother severely depressed. Andy was one of those ‘pass-the-parcel’ kids whose predominant childhood experience was rejection and abandonment.

Inevitably, he became a ward of the state, and then with the State of Victoria as his parent, he spent an abusive adolescence in foster homes, Homes and finally penal institutions including adult gaols.

As a ward of state, his teens were years of deep insecurity, abuse and self-abuse, leading to a cycle of self-destruction through drugs, addiction and petty crime. The one person who had any love for Andy was Mary O’Brien, a Ballarat youth worker – a ‘mother’ figure he could trust and the only hope of happiness and a positive future.

I won’t spoil it by revealing any more of the narrative, but suffice it to say that when Briggs goes on to say, “But the real Andy’s life was far more chaotic , and more grimly repetitive”, I had to say it would be hard to imagine how anything more destructive could have befallen him in his devastating 21 years.

This book could be slotted into the category of creative non-fiction. The question is why dress it up that way? Why does Ginger Briggs (to use her own words) “mess up” events and characters when she does very little to disguise the main characters and events? Why not a straight story? After all there’s no shortage of facts – and the author has been diligent in her research.

In her defence, she is a writer first and foremost – not an historian or psychologist. She has crafted the narrative to make the most of the tension inherent in the events and characters. And her creation of real-life teenage junkie grunge and spiralling desperation is brilliant.

But, for me, there was a certain level of dissatisfaction too. We know – because she tells us – that Mez is based on a real person, Mary O’Brien. And what a wonderful caring person she is. We know also that institutions such as Wakma (Warrawee) and Ironside (Turana) are real places thinly disguised. What would be lost by the use of real names and places?

In an Author’s Note at the end of the book, Briggs explains and confirms quite a deal of what we have already guessed. She changed the name of Mary O’Brien (to Mez) because she “invented some key elements of her story”. I interpret that to mean she used her license as a writer to tweak some parts of Mary’s story.

Briggs explains that Sylvia is really Kim Williams who lives in Scotland. Another friend, Spinner, is a fusion of three people – one died of an overdose, the second had gone incognito and the third was in prison.

Briggs tracked down the abusive social worker, Nigel Hayes, (like Briggs, I need to watch my words carefully) who is said to have groomed and sexually abused Andy and supplied drugs to other boys in exchange for sex. Unfortunately but understandably, Briggs did not supply his real name (authors have to live too!). He is said to be known to the police in Ballarat but has never been charged.

I am left with nagging questions. What if the book had been written as a factual account (even retaining the pseudonym Nigel Hayes)? Would police have made more strenuous efforts to investigate the allegations of sexual abuse and supplying drugs to minors? To interrogate surviving witnesses? To call to account his employers in allowing him to take young boys to his house alone for the weekend?

Nevertheless, this is a powerful, graphic and convincing account of how young lives can be utterly destroyed in a system that places so little value on the safety and welfare of young people who, through no fault of their own, cannot live with their own parents.

Briggs concludes that she has not come up with any answers to the many questions underpinning this book. But she has learned and shares with us two fundamental truths.

First, “kids need love and family – of whatever stripe – to thrive and grow.” And, in Andy’s case only one person, Mary O’Brien, was able to give him love consistently. But she was in no position to supply a substitute family. Her employment position and the circumstances she was in wouldn’t allow it.

Second, the state can never be a good parent. Who wants a mother who is “cumbersome, impersonal, bureaucratic, twelve storeys high and has a letterhead”?

To which she might have added: What kind of parents – with or without a letterhead – would be so derelict in their duty to a vulnerable young boy, or any child, that they could employ a paedophile to use and abuse him for his own gratification? And what sort of parents would have no interest in checking from time to time whether all was well?

What kind of parents would put a young boy in an institution where hard drugs went hand in hand with the toxic culture of sexual and physical abuse? And could not see to the very things he needed – love and affection, a decent education and enlightened supervision?

What kind of system has no understanding or concern that its ‘care’ institutions pave the way for vulnerable young persons to be locked up in cells in adult prisons where drug habits and other criminal behaviour are learned and reinforced – and young lives are ruined?

Highly recommended. But take care: there are events in this book that will wrench your guts.

One thought on “A Mother 12 Storeys High with a Letterhead”

Comments are closed.

A heart wrenching book about a person whom I love dearly and always will.