On 16 October 2025 I was invited to be the Guest Speaker at Ballarat Cafs AGM. Here is the text of my address.

I started preparing this talk on the eve of The Australian Rules Football Grand Final. My mind was attuned to events with four quarters. Here’s an orphan’s life in four quarters.

A Frantic 1st Quarter (1940-1943)

I was 2 years old in 1940 when I became a ward of the state—too young at the time to know a World War was raging, and another war was going on in my family. You don’t need the details, but it was not untypical of the times—involving alcohol, violence, family rows, the justice system, and military upheaval. After a stint at the Royal Park Depot in Melbourne, 6 months in the Andrew Kerr Home in Mornington, a period with our parents ‘on probation’, and several short foster care placements, we finished up in the Ballarat Orphanage in 1943. I was 4, Bob was 5 and Bill 8.

The Welfare was umpire—totally one-eyed, in a one-sided game. All the free kicks went to our father; our Mum’s side of the story went unheard.

I recall the day we entered the Orphanage front door, accompanied by a policeman. Everything was so big. In the Heritage Centre tonight, you can see the massive stained-glass window that greeted us in the foyer. When years later I described the Matron as big and frightening, I was roundly chastised by a close relative of hers who corrected me: she was a small woman. To a 4-year-old, she was massive and scary. Historic truth is multi-layered.

The 2nd Quarter: kicking against the wind (1943-1953)

My brothers and I had been thrown into the Ballarat Orphanage with 200 other grieving, angry, often confused children. Many had no idea why they were there. Like us, they were not orphans. Over the years, we swapped stories about parents. We knew some accounts were fictional. Any story was better than a shrug of the shoulders.

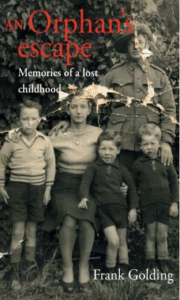

I shared that constant perplexity. Why was I there? When would it end? Twenty years ago, I wrote in my memoir, An Orphan’s Escape:

Prisoners know how long their sentence will be, but we did not. If only someone had sat down and explained. It was to take many years for us to learn the dark reasons why, when other fathers were coming home from the war to pick up their kids, we three were left behind.

Violence was rampant in the Orphanage—and it wasn’t only from the other children. The staff were not trained, several of them were older inmates—teenagers who had done their time, and a U-turn (maybe a blind turn) and were put in charge. I recall Bob having an angry physical exchange with a female staffer who told him, “You’ll be lucky to see your father ever again”.

Occasional visits from our parents were treasured, yet frustrating. Mum and Dad never talked about why we were in the Orphanage. After one visit, Superintendent Morton told me, “Your father upsets you; I’m going to cut out these visits.” My memory is sharp:

My cheeks caught fire… How could [he] know what I felt? … I wanted to challenge this man of authority, to tell him he was the one who upset me, not my Dad, but I didn’t know the words. Or have the daring. Humiliated, I said nothing and just went and sat on the wall so nobody could see my rage… The Orphanage upset me. The Superintendent upset me. Being an orphan of the living upset me. … Why couldn’t they see that?

Many years later, as a researcher, I found self-congratulatory media reports about the Orphanage in my era. Superintendent Bert Ludbrook told a conference in 1944 that the orphanage environment was equal to that in the average middle class home. In 1952, his successor, Eric Morton, likened the Orphanage to a boarding school.

As a child, I remember time passing slowly in the Orphanage—the weeks passing into months and the months stretching into years. I wrote:

Little by little, the hope and expectation of rescue ebbed away as we became used to being permanent inmates. Over the years, we grew into old stagers welcoming the new kids and showing them how to be orphans.

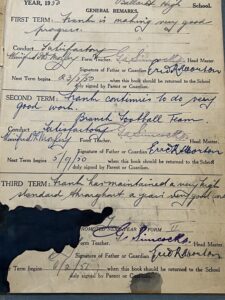

Being sent to the Ballarat High School in 1950 came as a very pleasant surprise for just a handful of us. My older brothers had already gone to grade 7 and 8 in the little school on the Orphanage site, which was the usual training ground before being sent out to work. High school gave us lucky ones a taste of normality, although lining up for the free books after all the other children had brought along cash to pay for theirs was demeaning. I did well at high school, but was a bit of an attention seeker. I had to carry back to Superintendent Morton a report about my bad behaviour. I literally blotted my copy book thinking I could cover up.

Yet, I was given the Most Honourable Boy award—the Orphanage Brownlow Medal. I had no idea why I won it, or who voted for me.

The premiership quarter—big games are won or lost in the 3rd Quarter (1950-1953)

In my memoir ( I wrote: “In time, we would outgrow the Orphanage”. Bill was gone one day, without being allowed to say goodbye. He was 14. I learned on the grapevine he had been sent to a farm in the Western District. A year or two later, my other brother Bob disappeared overnight too, but at least he was sent to a job in Ballarat and was living in the Orphanage Hostel at 28 Victoria Street. I could catch a glimpse of him on Sunday mornings when we marched down to St Paul’s on Bakery Hill.

My own departure was more spectacular—winning a trip to the Coronation of Queen Elizabeth in 1953 as a guest of a great sportsman, Walter Lindrum. I was the only ‘orphan’ on the tour. There was a back story which I was utterly unaware of at the time—about welfare officials uneasy about our parents eventually winning their long struggle to get us back if the trip went ahead. But it did.

I was an inmate in the totally regimented Ballarat Orphanage in April 1953 but became a free agent in London, at that time the centre of the western world. And when I came home in August, I was surprised to be told I was free to go home with my Mum and Dad—and my brothers would be there too.

The 4th and Final Quarter: After ‘care’ (1953 onwards)

I left the Orphanage on an emotional high. Yet in so many ways, it was a typical departure for a 15-year-old. I carried a suitcase with a change of clothes—but, more notably, I carried loads of emotional baggage with me. How do you come to terms with normal family life after such a stretch of time? Can such a family ever be normal again?

If you grow up in the ‘ordinary’ way, you have a deep-seated sense of belonging to a family with roots reaching back in time. You know who you belong to, and who belongs to you. You come home after school someone’s son or daughter, brother or sister, someone’s grandchild. You barely notice the accumulating social capital that shapes the way you see the world. Orphanage kids have to start learning all that—and so much more—when they leave.

There was plenty of blame and shame on both sides of the generational gap in our house in Main Road, but the silence that characterised our post-Orphanage family turned out to be more, much more, than blame and shame. In my recent book, That’s Not My Child: Five generations on the welfare treadmill (2024), I wrote about the shock of finding my mother’s two sisters and her five cousins had been inmates of the Ballarat Orphanage too in the late 1920s-early 30s. One of her sisters, Joyce, died there. And I found that my mother’s grandfather, at the age of 11, had been deemed a neglected child in the first wave of hundreds of children incarcerated under the Criminal and Neglected Children Actof 1864. Starting with that 11-year-old boy, five generations of children on my mother’s side were committed to out-of-home ‘care’. In short, the system produced and reproduced its clients.

Yet the overseas trip when I was 15 changed everything for me and for my family. Discharge from the Orphanage came on the cusp of leaving school—as my brothers had already done. They had been victims of the bigotry of low expectations within the Department. Here’s a memo I found in my files dating back to 1952:

Undoubtedly, all the boys will return to the mother and Golding in due course and it is just a question of whether he should be retained and given an education at the expense of the State when his future earnings will probably be collected by the mother.

Well, my education was at the expense of the State—but in the form of bursaries and scholarships that took me to Teachers’ College in Dana Street and then to Melbourne University. I would not have taken that path but for the will of my parents that I should do better that they had done.

I remember having an intense drive and determination to move on to something better, perhaps a strong reaction to the many years of having no hope. Maybe, too, there has been an unconscious kicking back against those who believed orphanage children like me would never amount to much.

My fortunate life as an adult—a career in education, school principal, academic, historian, writer and advocate; choosing to return to wonderful London to do a Master’s degree and then to Ballarat to do a PhD; being awarded an Order of Australia Medal at age 80—that’s not all down to chance. I have been fortunate over the years to meet and connect with many good people who wanted the best for me. I think of all the people who encouraged me—football coaches, school teachers, school inspectors, employers, colleagues, neighbours, good friends, and ultimately a family of my own.

I wish that all children who were once separated from their families were so fortunate.

People ask me why I have been an activist and advocate for Care leavers for the past 30 years. The answer is not complicated—it’s because it is still necessary, and I can do it. Perhaps this final quarter is never meant to end. After all, the earliest games of Australian football had no set time limits.