This is an updated version of a paper presented at the Annual Conference of the Australian Historical Association in Ballarat July 2016

Scene 1: 1956

I’m 18 and studying at the Ballarat Teachers’ College in Dana Street. It’s our weekly assembly. We all stand up to sing from our blue song-books: ‘Ballaarat’.

A city built on gold , She gave her wealth untold.

It made our land, so great and grand,, A Land of Liberty…

…So let your voices ring, In praise of everything.

At B.A. double L., double A.R.A.T.

Now, more than 50 years on, I can’t believe I sang along ‘in praise of everything’: just three years earlier, I had escaped from the emotional wasteland of the local Orphanage. But I sang as heartily and artlessly as any of my fellow teachers-in-training.

Scene 2: May 2015

The ABC’s 7.30 is on the telly. Leigh Sales stares down the barrel of the camera:

Tomorrow, the Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse heads to Ballarat. The regional Victorian city was home to some of the most notorious paedophiles Australia has ever seen. The effect of the abuse has been felt far wider than simply amongst the many victims. It’s intergenerational and it’s scarred the entire city.[1]

I travel to the County Court in Ballarat the next day with questions on my mind. Will these revelations shake the core beliefs about the city? Will Ballarat people, brought up like me on the stories of Eureka’s ‘wealth untold’ and the birth of liberty, ever look upon their city in the same way again?

How will historians of the future encapsulate this city? Will they agree with David Marr that ‘Ballarat in the 1970s…was one of the unsafest places for a Catholic child to grow up…’?[2] Why just Catholic children?

Scene 3: back to the 1850s

I put those thoughts on hold while I meditate on a largely invisible part of Ballarat’s history. Over the years, Ballarat has created some 19 institutions for its outcast children. I grew up in one of them.

It is painful to track the many ways we children were described. In the nineteenth century we were: criminal, neglected, destitute, abandoned, illegitimate, wayward, waifs and strays, urchins and vagabonds, street Arabs and youthful Bedouins. In the twentieth century we were children without sufficient means, or, more recently, children in need of care and protection.

You can tell from the labels that there was compassion, but it was never far from other emotions: fear, loathing and blame. As early as 1856, the Ballarat Star pleaded for compassion for the child casualties of the gold rush:

[P]rosperity and progress seem fairly to be our destiny. On the other hand, want and woe, vice and crime, are fearfully prominent in our community. In many a desolate tent…lies the subject of conjugal or parental desertion; or the unhappy victim of “sickness unto death,”…the most abject destitution.[3]

The Star also cited a number of cases of appalling sexual exploitation of young girls. The writer called on Ballarat’s civic leaders:

to initiate a project for the establishment of an institution which shall combine in its organisation the features of an orphan and destitute asylum, a female penitentiary, and an immigrant depot…

Three years later, the Star was running a ‘law and order’ crusade: to rid the streets of urchins who were, it said, …‘hastening with a fatal facility into an appalling precocity in vice and crime’.[4] Children had to be rescued from drunken fathers, vicious mothers, grown-up sisters working as prostitutes, and the ‘fatal influence of parental example’.[5]

With a Benevolent Asylum for the aged and infirm about to open its doors, the paper made a plea for a section to be set aside for children.

The Star made a distinction between ‘young vagrants and criminals’ on the one hand, and the ‘yet uncriminal orphans’ on the other hand. A separate reformatory and district orphanage were called for.[6]

The Benevolent Asylum opened in 1860, and by 1864 there were more than enough children to warrant a large school on site.[7] The Victorian government paid a subsidy to the Asylum of £3 per month per ‘orphan’, but it was clear that it was not desirable for children to be housed together with unmarried mothers (‘fallen women’) and people who were aged or chronically ill.[8]

These children were gradually removed. The older ones were indentured as servants. Some were despatched to industrial schools (including the new Ballarat Industrial School for girls which opened in 1869). Others ‘considered too “superior” for State care’ were transferred to the new Orphan Asylum which opened its doors late in 1865 at the other end of town.[9]

The Orphan Asylum’s Committee of Management made it clear from the outset that while it would take in children of ‘the Orphans of honorable parents’ (‘the perishing classes’) it did not want children of ‘the criminal and abandoned’ (‘the dangerous classes’). Parents and guardians would be put straight if they ‘labored under the impression that all Orphans, without regard to legitimacy, morals or respectability, were to be received’ into the Asylum.[10]

No child would be admitted without a birth certificate and a marriage certificate showing father’s name; and a doctor’s certificate declaring that the child was free of contagious diseases. The dichotomy of the deserving and undeserving poor lingered for decades. In 1943, when I was admitted to the Ballarat Orphanage (the tag was changed in 1909), my medical report declared me free of syphilis and epilepsy (but, ‘without blood tests’). At least the requirement to show a marriage certificate had been waived.

The Ballarat Orphanage warehoused more than 200 children at any one time, including many wards of the state. Most were not orphans: they were children whose parents were incapacitated through illness, or whose families were unable to look after them because of poverty or homelessness or family breakdown, desertion or – despite the original rules – children of unmarried mothers or those with a parent in prison.

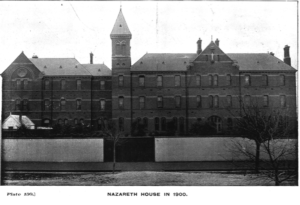

The Catholics, of course, had additional, separatist reasons for setting up two large institutions of their own: Nazareth House in Mill Street and St Joseph’s in Sebastopol.

Some institutionalised children were not locals. Despite serious opposition in Ballarat, a Boys’ Reformatory – ‘a receptacle for the scum of Victoria’[11] – was opened in 1879 on the site of the ‘Lunatic Asylum’ (previously the site of the Girls’ Industrial School). More than 100 boys were transferred from the gaol at Jika (Coburg) and many of them immediately absconded.[12] Later, some of the ‘reformed’ boys defied attempts to place them in passive service and these resisters were then housed at the Probationary School for Boys at Alfredton (1890-92).

Towards the end of the century, a private reformatory for girls, Brookside, was opened by a Mrs Rowe at Cape Clear, but after runaway girls told police about floggings, having their hair cut, being confined to bed, bread-and-water diets, and other brutalities, the reformatory closed.[13]

There was another large group brought in to Ballarat – Aboriginal children. It is instructive to read a speech by Catherine King, MHR for Ballarat. She told the Australian Parliament in 2008:

The four children’s institutions in Ballarat — Nazareth babies home, Ballarat babies home, Ballarat Orphanage and St Josephs — were all recipients of stolen generation children, many of them coming from as far away as Gippsland. I am ashamed to say that, as a 20-year-old working in what was the Ballarat Orphanage, I did not know its part in the history of this generation of children and I would like to add an apology for my ignorance and my lack of curiosity about the history of the institution I worked in.[14]

All told, over the years, tens of thousands of children spent time in one or other of these 19 closed institutions in Ballarat. And in addition, hundreds of destitute children were boarded out in private homes – a foster ‘care’ system which commended itself to government because it was cheaper than keeping children in large institutions. In 1914, for example, in and around Ballarat, there were nearly 500 children boarded out, many to their own mothers.[15]

Child and family welfare, then, has a substantial – but grossly neglected –presence in Ballarat’s history. The little that has been published is, with notable exceptions, benign, shallow and self-congratulatory – in some cases no better than lipstick on a pig – and blind to the widespread abuse of the vulnerable children taken into ‘care’ whose voices are never heard.[16]

A case in point is the responses to former inmates of the Ballarat Orphanage who requested Heritage Victoria (HV) in 2012 to place the site, now in the hands of private developers, on the Victorian heritage list. The Executive Director of HV delivered to the Heritage Council a contrary presentation which included 60 photographs, only two of which included people – and none of these were children.

HV was fixated on the built form of the place and it seemed incapable of seeing the value of the place to those who once lived there.

Charitable institutions in the nineteenth century were often constructed as grand and publicly visible buildings, reflecting the importance the society placed on providing for its underprivileged population.[17]

We former inmates begged to differ. We wanted the ‘remnant fabric’ of the place protected because what remained represented our extraordinary childhood – a total institutional experience removed from family and normal community. Behind the grand façade we ate, played, fought, slept, darned socks, washed and mended clothes, worked the farm and the vegetable garden, swept the yard, polished the floors and went to the elementary school on site.

We wanted to be able to tell our children in years to come about the communal baths and showers, lack of privacy, harsh discipline, physical and sexual assaults, the ever-pressing hunger, the chilling cold of the nights and wetting the bed, being separated from our siblings and missing our parents and not knowing why we were there.

The historian hired by the private developer asserted that the place evoked ‘mixed emotions’ and our valuing of the place seemed to be a ‘very personal response’ – as if that was our weakness.[18] Although both parties argued for its retention, the 1880s brick wall illustrates the gulf in understanding. The historian described it this way:

the pier-braced brick boundary wall to Stawell Street runs for approximately 100 metres, and most of this is in a weathered variant of Yorkshire bond with three stretchers separating each header. The wall was evidently punctuated by a gateway, as there is a clearly ‘filled-in’ part with much later brick and a dip in cornice height of about 30cm. This section is about 10m-wide in stretcher bond.[19]

I thought of all those children who experienced the wall in other ways. Some once clambered over it in search of freedom, or their parents. I was one of many who sat on the wall facing the tram terminus, hoping and yearning to see one of our parents alight.

The weeks turned into years before, one day, my father did step off a tram – and after he had gone, Superintendent Morton told me he would not be allowed to visit us any more if he upset me again. He didn’t ask me why I was upset. It certainty was not my father’s visit. When my two brothers and I reunited at the wall in the 1990s, none of us thought of the wall as ‘a weathered variant of Yorkshire bond’.

It is only recently, through a chain of formal inquiries[20] – and through the work of CLAN (Care Leavers Australasia Network) and other advocates — that the voices of survivors are now being heard, and those voices are seriously challenging the traditional narrative of bountiful compassion.

Full marks to Catherine King MHR for acknowledging that when she was 20 she was both ignorant and lacking in curiosity about the children she looked after. She was an insider, working close to these children; imagine what that might say about other citizens of Ballarat who did not take the trouble to look over the wall.

When the royal commission came to town, many Ballarat citizens and historians were totally unaware that the golden city sat on a time-bomb of institutional child abuse.

Can we be optimistic that in future citizens of Ballarat will be more curious, and historians more inquiring, of the ‘care and protection’ provided to our most vulnerable children?

Footnotes

[1] The ABC’s 7.30 18/05/2015.

[2] David Marr in Conversation with Heather Ewart at The Wheeler Centre, Melbourne, 21.10. 2013, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aYz4gn-HlDY

[3] Ballarat Star, 28.8.1856: 2.

[4] Ballarat Star, 5.12.1859: 2.

[5] Ballarat Star, 22.10.1859: 2.

[6] Ballarat Star, 12.12.1859: 2, 3.

[7] Doreen Bauer, Institutions without walls: A brief history of geriatric services 1856-1985, Waller & Chester, Ballarat

[8] Dorothy Wickham (2003): Beyond the Wall: Ballarat Female Refuge, A Case Study in Moral Authority. M.Phil. Thesis, ACU, Melbourne: 54.

[9] Wickham (2003): 55.

[10] Ballarat Orphan Asylum, Committee of Management, 2nd Annual Report 1866:12. See also Nell Musgrove (2013) The Scars Remain: A long history of forgotten Australians and children’s institutions, Melbourne, Australian Scholarly: 18-26.

[11] Ballarat Star 23.12.1879: 2; Ballarat Star 19.9.1879: 2.

[12] Ballarat Star 25.9.1879: 3; 5.12.1879: 2; 15.12.1879: 2, 7.

[13] The Argus 17.7.1899: 5; 2.8.1899: 4. See also Sophia Callaghan (2004) Towards submission and servitude: The punitive reformation of juvenile female offenders at the Brookside Reformatory for Protestant girls, 1887-1903. BA (Hons) Thesis, University of Melbourne; and Helen Doxford Harris, Criminal & Other Case Files at: http://helendoxfordharris.com.au/archives/240.

[14] Hansard, 14 February 2008: 457. See also Ballarat & District Aboriginal Co-operative Ltd., Faded Footprints: Walking the past, (The Co-operative, Ballarat, n.d. 2008?). My own memory is that around 10 per cent of the children I lived with in the Ballarat Orphanage were Aboriginal: Frank Golding (2005) An Orphan’s Escape: Memories of a lost childhood, Lothian, Melbourne.

[15] Ballarat Courier, 25.12.1914, p. 7. See also Shurlee Swain (2012) ‘Making Their Case: Archival Traces of Mothers and Children in Negotiation with Child Welfare Officials’, Provenance: The Journal of Public Record Office Victoria, issue no. 11.

http://prov.vic.gov.au/publications/provenance/provenance2012/making-their-case; see also Department for Neglected Children & Reformatory Schools, Annual Report for the Year 1916: 3.

[16] See e.g. Wilson, Jacqueline Z., & Frank Golding (2015) ‘Caring about the Past or Past Caring: The Contested Narratives of Memory’, in Shurlee Swain & Joanna Skold (eds), In the Midst of Apology: Professionals and the Legacy of Abuse amongst Children in ‘Care’, London: Palgrave Macmillan.

[17] Heritage Victoria, (2011) Executive Director’s Assessment Report: 5.

[18] Lovell Chen (2011) Former Ballarat Orphanage 200 Victoria Street, Ballarat East: Conservation Management Plan Prepared for Victoria Street Developments Pty Ltd: 95.

[19] Lovell Chen (2013) Former Ballarat Orphanage 200 Victoria Street, Ballarat East: Conservation Management Plan Prepared for Victoria Street Developments Pty Ltd: A30.

4 thoughts on “Ballarat’s Difficult History: Outcast Children”

Comments are closed.

Dear Frank,

I know this is public and i may not get a response from you but hoping to get a response from someone about these magnificent but painful buildings.

First my name is Kayla and im 23 year old. From an early age history has always interested me and is now a hobby that im extremely passionate about aswell as people. Any kind of information i can find im willing to explore further. Some things i have found about other things are amazing but yet painful from the stories i have heard and found for myself.

I understand if you and or anyone else reading this would be difficult to speak about but i would really love to hear your stories and how life was for you there as i have visited the site a few times now. Please note this is strictly my own interest and by no means will i share what your willing to say to me to anyone else as of course its very much a magnificent time of your life and history sharing with a stranger.

I look forward to speaking with you and or someone about this big part of history and thankyou for your time in reading this.

Yours Sincerely,

Kayla Gates

Hello Kayla. Thank you for your interest. There are plenty of ways you can get more information about this site and its former residents. For example, most libraries will have a copy of my memoire, “An Orphan’s Escape: Memories of a lost childhood” which is a detailed account of what it was like for me. Ballarat Child & Family Services in Lydiard Street Ballarat has a Legacy & Research Centre where you can see an array of artefacts and memorabilia from the old orphanage. In general, these orphanages and children’s Homes are well described in the Senate Report, “Forgotten Australians (2004) which is online -just google it. You can also find many historical articles about the Ballarat Orphanage and other Homes on Trove. You may also like to browse the website of CLAN (Care Leavers Australasia Network) http://www.clan.org.au which will give you a good feel for the psychological legacy of a childhood in “Care”. I hope that all helps. Thanks again for your interest.

Thank you this brilliant essay. You have written in the research and unpacked the myths that continue to harm.

The values important to those who are set to gain power and money are clearly devastating to all people in society.

They are still taking away the culture we are a product of. What has been continually been done to children, to those a bit different, to others with little or no value on the meanings of the history and culture that has developed in the context you experienced.

I have to salute you. You have done this piece with your life.

Thank you again.

Sue

This is well documented and historically well written. Perhaps we also need to take a look at why children were made state wards, what was recorded in their files at the time of being removed and the perception of the children who are now adults and what their account may be of their history and why they were removed.

I know the period of 1960/65, when l was a t the Ballarat Orphanage there were discussions amongst other residents about why they were removed. For several residents the reason was because of domestic violence, usually by the father towards the mother. this was the case for myself and siblings and the reason for our removal. However, this is not recorded in our files. The files actually are very mother blaming.

While sitting on the wall as you often did Frank, l have a clear memory of my mother stepping up onto the tram and winching in pain. She had been beaten the night before, she still managed to bake cakes the night before and bring enough things for us to have a barbie at the stockade. No, you will not find this in our files.

Frank as you are aware, l am a strong believer in recording history, l feel there needs to be more of a focus on the later years of the Ballarat Orphanage maybe from the 1960s on to the closure in the mid 1980s. Looking at the files and reality and perceptions of past residents.. Why was there so much abuse over this period of time. We also need to focus on the achievements of Orphanage and how others view their time in the home.