Re-creation of the Ballarat Orphanage Arthur Kenny Avenue of Honour

In the 150th year of its operations (first known as the Ballarat & District Orphan Asylum in 1865) Ballarat Child & Family Services (CAFS) has re-created the Avenue to commemorate the service of old boys of the orphanage who served in World War 1.

With the backing of the City Council, a new avenue of 106 Algerian Oaks lines Fortune Street leading from Fussell Street towards the Mt Xavier Golf Club. This is about 300 metres from the site of the original avenue.

The avenue was officially opened by Maj. General Simone Wilkie an Honorary Ambassador for CAFS in its 150th Anniversary year. The planting coincides too with the Centenary of Gallipoli.

I was asked to provide some background to the history of the avenue and make some comments on the old boys. Unfortunately, about halfway through my speech, the skies opened tipping a bucket on the crowd of several hundred people (including students from two schools) and I cut my speech short. I insert here what I would have said – together with some more photos.

Advertisement for my Twilight Talk at the Art Gallery, Ballarat on 29th April.

Australia at War Twilight Talks at Art Gallery of Ballarat in conjunction with the exhibition Australians at War, 1914-1945.

A series of twelve talks at the historic Ballarat Art Gallery in Lydiard Street, on Wednesday evenings from 8 April to 24 June, (entry by donation, with wine and cheese served).

As part of the series, I was invited to present a talk in the series on 29 April entitled ‘Making men out of boys: Ballarat Orphanage volunteers in World War 1’. I talked about what made the experiences of the 105 Orphanage ‘old boys’ distinctive as a group, and how they were commemorated by the Orphanage.

It is interesting to observe the changing tone in the Orphanage’s Annual Reports as the year progressed.

1915 – We know of forty of the old boys who have enlisted. Some of them have been wounded and one has already given his life in his country’s cause. Several of the band boys are in the bands of the various battalions. One boy received his commission as a lieutenant and one aged 20 has just left with the 400 permanent men as a serjeant artificer (Annual Report 1915)

1917 – Still more of our boys have left these shores to fight for king and Empire. Many never will return, having given their lives in the grandest work of all, defending their country and fighting for Right. Others have returned – some with limbs missing, others with health impaired. All, both those going and those returning, have managed to visit their old home and be either speeded on their way with good wishes or be welcomed home. We honor them every one. (Annual Report 1917-18)

1919 – It has been great pleasure to welcome back so many of the old boys who have been away at the front. Some have returned who have been in the fighting line from 1914 to 1918, some have gained commissions, some are maimed, others have lost their health, while still others seem to have gained by their experience. We welcome them all home again and it shows that they still love their old home and have happy memories and feelings of gratitude when they so uniformly return to visit it after their years of absence. Some have been away for as much as twenty five years returned to recount their adventures and experiences (Annual Report 1919)

This talk was independent of the 150th anniversary celebrations described above, but happily sits alongside those events particularly the re-opening of the Avenue of Honour in later in 2015.

♣♣♣

https://frankgolding.com/orphanage-old-bo…old-girls-at-war/Making Men out of Boys: Soldiers from the Ballarat Orphanage in World War 1 (This talk, and various versions of it, has been presented at various dates and places).

100 boys from the Orphanage volunteered for the war. They enlisted earlier and younger than the rest of Australia as a whole – and had a greater rate of death and casualty. Read it here.

♣♣♣

Making Men out of Boys – Multiple Presentations

2015 is the centenary of Gallipoli and the 150th anniversary of the opening of the Ballarat Orphanage (or Ballarat & District Orphan Asylum as it was originally labelled). It is not surprising that I have been asked to present my research on the Old Boys of the Orphanage who enlisted in World War 1.

What is surprising is the number of times I have been asked to repeat the presentation. A successful presentation at the Ballarat Art Gallery in April led to others in July, August, October and December – and update in Ballarat again in April.

The Ballarat Orphanage Avenue of Honour (1917) has been moved

The so-called Arthur Kenny Avenue of Honour pays tribute to the old boys of the Ballarat Orphanage who fought in World War 1.

The Avenue has been relocated to Fortune Street, Ballarat East – the road off Fussell Street leading up to Villa Maria and the Mt Xavier Golf Club. This is a more accessible site and puts to rest the old problem of the original avenue being erected on Crown Land.

The Avenue stretches about 400 metres along Fortune Street and for each soldier a tree has been planted with a plaque erected by the Ballarat City Council.

My Speech at the Re-opening of the Ballarat Orphanage Arthur Kenny Avenue of Honour, 3 August 2015

It’s so good to see family descendants here today.

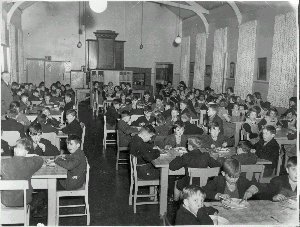

- I am happy to be here today as a former resident of the Ballarat Orphanage where I lived for 11 years from 1943 to 1953. I well remember looking at the Roll of Honour to the ‘old boys’ who served in WW1. It hung on the wall of the Dining Room. We read the 93 names as we came forward in the queue to get our food three times a day.

- I calculate that I would have looked at that Roll more than 11,000 times. Yet, strange to say, at that time—some of it during the 2nd World War—none of us knew anything about this Avenue of Honour. I’ll say why in a moment.

- I learned the story of the Avenue not as a resident, then, but as an historian coming back decades later to collaborate with a range of good people to prepare the re-Discovery event in 2012—which you can read about in the newly-revised booklet.

- It’s a story that began with a fund-raising idea—an Arbor Day on Crown land which the Orphanage leased here at Mt Xavier. It would raise money on the day—as well as produce a harvest of pinewood when the trees matured.

- Quite late in the process, the Committee decided to create an Avenue of Honour as a tribute to the ‘old boys’ fighting overseas—although at the last minute, the Avenue was named in honour of Arthur Kenny, the Orphanage Superintendent, who of course was not a soldier.

- The local papers reported that there were “more than 100” Orphanage ‘old boys’ at the War. But when the Governor-General, Sir Ronald Munro Ferguson, opened the Avenue in August 1917, only 78 ‘old boys’ could be named.

- We know that when people leave institutional ‘care’, they scatter far and wide. Only 36 ‘old boys’ enlisted in Ballarat. Some were interstate; one enlisted in New Zealand; another was at sea with the Navy when war broke out and he was enlisted by default. So it was hard to get the names right when this Avenue was created. Some names were incorrect. Many names were missing.

- Through the exhaustive research by Sharon Guy and myself we now have an accurate list: 105 ‘old boys’ were accepted as volunteers of whom precisely 100 went overseas. Another was rejected on medical grounds but went to England as a civilian munitions worker. I’m happy to count him in as one of ours.

- It was quite a day, 3rd August 1917, a gala occasion on which over 1,000 non-military dignitaries, politicians and donors were also honoured—some with as many as four trees planted in their name.

- But, there was always opposition to it. Some argued that the Avenue of Honour Orphanage should not be allowed to alienate Crown Land. There were disputes over who should manage the land. When Arthur Kenny, the driving force, died in 1925, the Avenue of Honour was soon lost from public consciousness and gradually fell into disrepair.

- This was a great pity because many of the boys did not have family to put their name forward when it came to memorials. At the grand Ballarat Avenue of Honour leading from the Arch of Victory, only one in every three of the soldiers who were ‘old boys’ of the Orphanage had a tree planted in his name. This dedicated Avenue here at Mt Xavier fills a gap for the many who were overlooked.

We know quite a lot about these Ballarat Orphanage soldiers. They were a remarkable group when you line them up against the 330,000 Australian volunteers of 1914-1918.

Consider their enlistment patterns. And remember that single men under 21 needed parents’ or guardians’ consent to enlist.

- When they enlisted, some of the ‘old boys’ did not know the whereabouts of their parents. Only 10 of them sought consent from a parent—one refused.

- 33 of them gained the consent of guardians and next-of-kin—four of them from Orphanage Superintendent Kenny. There were some dubious ‘guardians’ and next-of-kin—including employers, siblings, friends, girlfriends even.

- The rest gained enlistment through a mix of street smarts, fibs and aliases.

- They did more than their fair share. Just under 40% of all eligible Australian men enlisted in WW1, but more than two-thirds of the eligible Orphanage boys enlisted.

They volunteered far sooner and at a younger age.

- A quarter of the Orphanage boys enlisted in the first phase of the war—i.e. twice the rate of other volunteers in the same period.

- There were twice the proportion of Orphanage teenagers as other Australian teenage soldiers. They were very keen. Percy Lowen is a good example. He pitched a yarn to the recruiting officer. He was 18 years and 9 months old, he said. His parents were dead so he brought along a friend as next-of-kin to give consent. Percy fessed up in 1946 that he had been just 16 at the time. In fact, his birth certificate shows he was really 15 years and 10 months.

- It’s remarkable to think that, in 1914, there were 13 boys still living in the Orphanage who would eventually enlist by 1918 – including the last two – the 99th boy and the 100th boy – who only reached the first port of call when they were told the armistice had just been signed. So they came home without firing a shot—or being shot at.

War changes things for everyone.

- The Orphanage Roll of Honour lists 16 ‘old boys’ who died. But AIF records showed, sadly, that 20 died. 84 of the ‘old boys’ were wounded or hospitalized—much higher than the national rate.

But soldiers are never the only casualties of war. Research shows a very strong connection between children’s welfare and war. This is a general point, not exclusive to the Orphanage men.

- Apart from the loss of husbands, fathers, brothers, many families had to deal with soldiers’ disabilities, alcoholism, violence, depression—undiagnosed PTSD.

- Desertion and divorce rates increased rapidly; and numbers of children in out-of-home ‘care’ rose dramatically after the war.

- The First World War created the next generation of children to go into ‘care’—and many of these would go on to fight in the Second World War. Another story.

We should not end on that somber note. The war gave some of our ‘old boys’ opportunities to show their mettle – and they did.

- Three became officers and 13 became NCOs. Not bad going for young men from humble backgrounds.

- Harry Reed was awarded the Military Medal for bravery in the field.

- Some thrived after the War e.g. Pte William Prowse became a Life Governor of the Orphanage.

- Up until now, some had never been acknowledged. But it’s never too late to show respect. In this Avenue of Honour—re-discovered, renovated and about to be re-opened—we are remembering them!

Photos by Frank Golding (except the Dining Room – courtesy CAFS)

♣♣♣

A Winner!

The City of Ballarat has announced the winner of the 2016 award for Conservation of a Heritage Place, Historic Collection or Tradition (Intangible):

Arthur Kenny Avenue of Honour Recreation, Fortune Street, Ballarat East- Child and Family Services (CAFS)

The citation reads:

Once lost, often forgotten – now found, re-loved and retold at a nearby site, with new trees, new plaques and new “Avenue“, this project contributes to the extensive legacy work being undertaken by CAFS. The process of the project has involved thorough research and ensures the avenue will be remembered long into the future with strong community involvement. The process has been well interpreted and we know more about this avenue and those associated with the Ballarat orphanage than ever before.

More information here.

♣♣♣

CALL FOR SOLDIERS’ NAMES

I am working with Care Leavers Australia Network (CLAN) to compile a comprehensive list of men and women who were raised in orphanages or children’s Homes and who served in WWI and WWII.

If you have any relatives who grew up in orphanages or children’s Home and fought for Australia, or know of Rolls of Honour or Honour Boards erected by orphanages, please contact me or CLAN. We aim to make a memorial page on the CLAN website.

Contact me through this website or CLAN on 1800 008 774 or 0425 204 747 or support@clan.org.au

♣♣♣

MAKING MEN OUT OF BOYS (8 April 2015) This a work in progress. It focuses on one aspect of the larger project – the youth of the Ballarat Orphanage soldiers of World War 1.

Superintendent Kenny dubbed them the Last of the Mohicans, but Percy and Bertie Cooper and their sisters, Lily and Sophie, never understood The Mister’s joke. The Coopers had no books of their own in the Ballarat Orphanage. Learning to read stories from the Bible and Deeds that Won the Empire was deemed sufficient for the world they would inhabit in later life.

The Coopers had not seen their father for many years. They thought he was dead. He had tried to look after them when their mother died; but finally the Orphanage was the only way. Bertie was the youngest, just five. There, among the masses, he would come to see less of his siblings as the years went by until he almost forgot who they were to him.

Billy Broker was more like a brother, especially after The Mister told Percy Cooper he was old enough to earn his keep at 14 and sent him out to service. Billy Broker had come into the Orphanage the same year as the Coopers. He was Bertie’s age when his father had died. Billy and Bertie looked out for each other over the years, the one keeping watch for the other when they raided the apple orchard at Woodman’s Hill.

When Bertie and Billy were nearly 13, a new kid, Ivo Ignatius Bibby, joined their small raiding parties – but only after a sharp bout of fisticuffs had proved his merit. Ivo Ignatius was his name, and he wasn’t going to let any snotty-nosed brat make fun of him. Not like the ‘Yard Boys’ – Charles Foott, Harry Foott and John Foott. Harry was called the middle leg – and his brothers laughed along with the mob.

Within a year, Bertie Cooper, Billy Broker and Ivo Ignatius Bibby had become so tight in one another’s company that The Mister dubbed them The Three Musketeers. And when the war broke out, had they been old enough, they would have joined the excited rush to the AIF recruiting stations. In 1914, no one imagined that the war would last so long that fifteen boys still living at the Orphanage would grow old enough to enlist – including Bertie, Billy and Ivo Ignatius.

Many boys from the Orphanage had already shown them the way. Ballarat ‘orphans’ still in their teens enlisted at more than double the rate of the nation’s teenage recruits. And they were quicker to put their hands up. More than 20 former Orphanage residents enlisted in 1914 – twice the proportion nationally. Another eleven Orphanage boys enlisted in the first half of 1915.

We should not be surprised by the boys’ enthusiasm to ‘have a go’ given the militaristic culture of the institution. From the outset, drills were part of daily life and, from 1894, The Mister appointed military instructors to provide gymnasium classes. In the 20 years up to 1914, the leading instructor was Sergeant-Major William Brough of the Ballarat Militia, a Boer War veteran and policeman. The Mister set up a brass band in 1900 and in 1909 the Orphanage adopted “a rousing marching song” of its own.[1] The Argus may have been closer to the mark than it realised when it commented in 1889:

when the time comes, [the children] will go out to fight the battles of the world, well prepared physically, and armed with a store of useful, practical knowledge.[2]

In all, 105 ‘old boys’ enlisted; and of these, exactly 100 embarked for overseas to fight the battles of the British Empire.

All single men under 21 were required to have the written consent of a parent or guardian – and this was always going to be problematic. Just 25 of the 43 Orphanage boys who admitted being under 21 gained consent, although it is likely that some of these forged the signatures.

Twelve of the boys gained the consent of a ‘guardian’ – a capricious term. Some guardians were self-appointed, others were nominated for the occasion: a sibling, grandparent, uncle or aunt, and some just friends. The Mister gave consent for a number of boys, including both of the boys he employed at the Orphanage, Walter Granland and Harry Reed. Harry nominated his brother William Reed as next-of-kin; but when Harry won the Military Medal for “conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty”, the citation was sent not to his next-of-kin, as was the usual practice, but to The Mister. Even when The Mister gave his consent as guardian that was no guarantee that the boy was 18. Alf Glassford, for example, was barely 17. The Mister also signed for Percy Cooper, Bertie’s then 20-year-old brother, even though he had left the Orphanage in 1912.

Eleven of the boys under 21 gained consent from their nominee as next-of-kin, a term even less precise than guardian. Percy Lowen, for example, told the recruiting officer his mother was dead and he did not know where his father lived. He brought along a friend as his next-of-kin to sign the consent form declaring himself 18 years and 9 months old. In 1946, Percy confessed that he was just 16 at the time. In fact, he had not yet had his 16th birthday.

Thomas Watson and his younger brother Norman were typically inventive. Both claimed to be 18: Thomas enlisted in April 1916; Norman enlisted in March 1917. Both said both their parents were dead. Thomas nominated an aunt as next-of-kin while Norman nominated Thomas. Norman was not entirely convincing and he was asked to clarify matters. In his statement, he maintained he was 18 but confessed:

I told [the recruiting sergeant] that my mother left me when I was 13 months old and I have only seen father twice during my lifetime. I have been out working since I was able to and I generally lived with the people I worked for…My grandfather… looked after me until I was seven years old, and then my uncle William Watson now deceased had me placed in the Ballarat Orphanage. I am 18 years and 5 months and was born at Ballarat. My mother’s name was May Watson, she lived at Ballarat. I do not know my parent’s [sic] whereabouts. I think my mother has married again and lives somewhere near Colac. My father’s last address was Mount Magnet, West Australia. My next of Kin is my brother Thomas Watson at present on active service in France.[3]

Their ‘dead’ father was indeed living in Mount Magnet and, hearing of Norman’s enlistment, wrote to the AIF in May 1917: ‘This is to certify that I am willing to give my son Norman Edward Watson, age seventeen years, my consent to enlist in the Australian Military Forces.’ Confirmed in their suspicions, the AIF could not continue with someone known to be just 17, even with his father’s consent. They discharged Norman who had already served for 102 days. But three months later, he was back in the army – a girlfriend was his next-of-kin – and within a few weeks he was on a ship bound for the Middle East. A number of other under-age boys managed to volunteer for service without anyone’s consent at all. Some recruitment officers were known to turn a blind eye if a lad was strong and keen.

The system itself turned a blind eye to Lindsay Irving’s enlistment. He had joined the Navy as a ‘ship’s boy’ in 1912 two days before his 16th birthday. On his 18th birthday, 3 June 1914, he signed up for seven years’ service. Two months later when war was declared, Lindsay was automatically assumed to be ‘in’ for the duration. His widowed mother living in Ballarat was not asked to approve his war-time enlistment. Seaman Irving did not return to his mother until February 1919.[4]

The Government relaxed the recruiting regulations in May 1918 to allow men under 21 to enlist without the consent of parents or guardians. They were now able to join up at 18, but could not serve at the front until they were 19. The Minister for Defence, Senator Pearce, afterwards ruled that youths could be enrolled without consent if they proved they were over 19.[5]

And so it was that the Three Musketeers, now 19, were finally able to enlist. They didn’t know it then, but they would be the last three boys from the Orphanage to put on the uniform.

Bertie Cooper had been discharged from the Orphanage to his older sister Sophie (now Mrs White of NSW) back in August 1915. He was working as a farm labourer when he heard about the new rules. By 4 July 1918 he was in training camp impatient to join his brother Percy on the Western Front. For months, he endured what he thought were pointless drills and route marches. Finally, on 22 October 1918, he was among the 900 reinforcements aboard the troopship Boonah which sailed from Adelaide bound for the Middle East. When the ship arrived at Durban on 16 November, to his utter consternation, Bertie was told that the Armistice had been signed five days earlier. To make matters worse, he would never set foot on foreign soil. ‘Spanish’ influenza was rampant in Durban and the ship was quarantined. On 24 November, the Boonah steamed back to Australia. During the journey home the dreaded virus erupted on board with devastating results – hundreds were stricken and 27 soldiers and four nurses later died.[6] Bertie was bitterly disappointed that he did not make it to the front, but he could say he had been with some who died for Australia.

Meanwhile, Ivo Ignatius Bibby was aboard the troopship Carpentaria when it set sail from Sydney on 7 November 1918 bound for Europe via the Panama Canal. Just off Auckland, the news of the Armistice came through by wireless. Like Bertie, Ivo never set foot on foreign soil because Auckland was also hit by the deadly influenza epidemic.[7] The troops were transferred at sea to the SS Riverina to return to Sydney. After a short period in quarantine, the Riverina was declared clean and the troops disembarked on 28 November. Discharged in time for Christmas, Ivo Ignatius glumly shared the roast turkey with an even glummer roommate in their boarding house in Footscray.

That roommate was none other than Billy Broker. Billy had left the Orphanage in November 1914 and bided his time to ‘do his bit’. But, despite his enthusiasm, Billy would not even set foot on a ship. His mother put her foot down. Under the new rules he knew he didn’t need his mother’s approval, but Jane Broker wrote to the State Recruitment Committee in July:

I am a widow and an invalid. I desire to have my son with me until he is 21 as he is my whole support.

Technically, she had no rights, but a sympathetic recruitment office thought her claim should be checked. How much of his pay did he give his mother? he was asked. He did not dillydally with his answer: 10/- out of £2/10. A simple enough exchange, but, together with a bout of illness, the process caused Billy’s enlistment to be delayed. By the time he was accepted, on 25 September, Billy’s dreams of getting to the front had sailed away. He sat around in suburban barracks, cleaning his rifle, attending parades, for 91 days, awaiting the inevitable notice: ‘surplus to requirements’ and demobilisation. They let him go home on Christmas Eve 1918. Around the Christmas dinner in their ‘civives’, Bertie Cooper and Ivo Ignatius Bibby could at least talk about their all-expenses paid sea voyage, but what could Billy Broker say about his 91 days military service?

ΩΩΩ

In 1919, the Orphanage was welcoming back many of the old boys who had been away at the front. It was time to take stock:

Some have returned who have been in the fighting line from 1914 to 1918, some have gained commissions, some are maimed, others have lost their health, while still others seem to have gained by their experience. We welcome them all home again and it shows that they still love their old home and have happy memories and feelings of gratitude when they so uniformly return to visit it after their years of absence. Some have been away for as much as twenty five years returned to recount their adventures and experiences.[8]

And the 20 who did not come home? Not a word was spoken of them. Perhaps the grief and the guilt were unspeakable.

Many of the surviving boys had grown to adulthood in the trenches. As early as February 1916, Dr. John Richards, an honorary Medical Officer at the Orphanage and an officer in the Army Medical Corps, told the Orphanage committee that he had seen many youths at Gallipoli who were not strong enough to carry their knap-sacks in storming heights. Some had collapsed and were hospitalised, he said. In Richards’ opinion no recruits under 20 years of age should have been allowed to go to the front.[9] The bullish Prime Minister, Billy Hughes, conceded in Parliament on 1 September 1916, that:

…it would have been better if the boys under 21 had not been sent. They succumb more quickly to hardships and do not recover from wounds as rapidly as older men. The fight is for grown men.[10]

And yet much worse was to come in the slaughterhouses in France and Flanders.

For some, the war did not end with the Armistice. Bertie’s brother, Percy Cooper, for example, had enlisted in May 1916 and was involved in the last major action of the War in France. The Mister had approved his enlistment because both parents, it was said, were dead. However, in December 1918 his father wrote to the AIF from New Zealand asking for ‘full particulars’ of Percy’s death. He was thrilled to learn that he had been misinformed. In September 1920 Percy returned to Ballarat and married his sweetheart, Doris. But he was not the young man who had left to fight the battles of the Empire. Without notice, he deserted Doris and their two small children. In 1926, Doris wrote to the AIF from Ballarat pleading with them to

…help me trace my husband Percy Cooper who has been missing from home since first week in September 1925 & suffering from nervous breakdown…Please help me if you can for the sake of his little ones & for what he did at the war. I am ill and long for his return.

Percy did not return. Many years later, he wrote to the AIF from New Zealand to say he had been with his father for the past 22 years. Was the boy making up for a childhood lost, or was the man still fighting a war that would not end?

[1] Morris, Ethel, A Century of Child Care: The Story of Ballarat Orphanage 1865-1965, The Committee, Ballarat 1965; and the Ballarat Orphanage Annual Reports of the respective years.

[2] Argus (Melbourne), 8 June 1889: 10.

[3] Unless otherwise indicated, quotations are from individual soldiers’ dossiers held by the National Archives of Australia, Series B2458.

[4] Courier (Ballarat) 20 February 1919: 4.

[5] Scott, 1941: 460. Senator Pearce’s clarification is in the Argus, 10 May 1918: 8.

[6] Darroch, Ian, The Boonah Tragedy, Access Press, Bassendean, 2006.

[7] Advertiser (Adelaide), 19 November, 1918: 6; and 27 November 1918: 7.

[8] Ballarat Orphanage Annual Report, 1918-19: 6.

[9] Argus, 20 March 1916: 2.

[10] Argus 2 September 1916: 19. He was explaining why the conscription proposal would not apply to men under 21. A few days later Hughes appeared to resile from that position: Argus, 7 September 1916: 8.

♣♣♣

When organisations like the RSL and other civic groups memorialise service men and women who served in theatres of war, they can only get so far when relying on official records. They often rely on families to provide further information.

In the case of service men and women who grew up in orphanages and children’s Homes, many came from families so fragmented or disrupted that no one was in a position to know about their enlistment. A few Homes erected Rolls of Honour and a couple even created their own Avenues of Honour, but in most cases these have fallen into disrepair or have long been forgotten.

The Ballarat Orphanage Avenue of Honour launched in 1917 and lost from around 1925 was recently rediscovered and relaunched. You can obtain a copy of the commemorative booklet, The Re-Discovery of the Ballarat Orphanage’s Arthur Kenny Avenue, from Sharon Guy at Ballarat Child & Family Services, 2012, here.

The Booklet contains a brief bio of just over 100 ‘old boys’ who served in World War 1 (no ‘old girls were discovered).

The analysis of their service showed that on average they enlisted younger, earlier and at a greater rate than other Australians. My extended paper on this, “Making Men out of Boys”, is published here.

Has anything been done for those orphanage boys that served in WW11 Frank?

Thank you for the background information. My grandfather was John Roy Douglas who was in Ballarat Orphanage from about 1899 when aged 2 after his mother and sister’s death. He did have an older sister Ada also there. He enlisted in 1918 and Ii was informed a couple of years ago that he had a tree !

I am visiting Ballarat next week specifically for the purpose of visiting the Avenue of Honour and to pay my respects.

Hello Liz, I hoped you enjoy the visit to the visit to the Avenue of Honour. Just to remind you, this is located in Fortuna Street Mt Xavier on the road to the Mt Xavier Golf Course (not the main Avenue of Honour on the western outskirts of Ballarat). Do you have a copy of the booklet I helped put together for CAFS? I wrote a brief paragraph on each of the 105 Orphanage soldiers. Your grandfather is on page 17 of the revised version. CAFS might be able to supply a copy. The flu that he contracted at the end of the War was a much more serious disease than it is today. it was a killer, so your grandfather was lucky to come home alive! Best wishes

Frank

This is really useful, thanks.

Thank-you for this great insite. I only recently found out that not only was my Grandfather in the the Ballarat Orphanage, but, he was also one of the 105 “Orphanage Old Boys”. Going by his birth certificate he was only 16 years and 11 months when he enlisted, the paperwork was supposedly signed by his Father.

Stan, what was your grandfather’s name?

Hi Frank, his name was Albert Gordon Grant

Hi Stan, thanks for that. Have you seen the booklet that we put out on the 105 soldiers? I wrote a very short bio about each of the 105 and included a little bit about each one’s orphanage history and war service.

Yes Frank, I did see that, it was very helpful. I have also been in contact with Sharon Guy and she is helping me with his history at the orphanage.

A fascinating insight into the early history of boys from the Ballarat Orphanage pulling all sorts of tricks to be allowed to go off to war and fight as Men. Interesting to read that the System itself turned a blind eye to allow underage boys or boys without proper consent to go off to fight a war, nothing ever changes, the system still turns a blind eye on institutional care. Amazing too, is the silence for the twenty that never returned who fought and died in the trenches of a foreign land. The history of these brave boys and men has now been documented for prosperity.

Well said, Brian. Most of these boys missed out on getting a tree in their name on the Ballarat Avenue of Honour because they had no one to speak up for them.