Whose History is it, Anyway? Global Records Access Information Exchange, 28 September 2021, Frank Golding OAM, PhD

When I started thinking about what I could say in my allotted 10 minutes today, I thought I might discuss the first 5 of the 10 rights in the CLAN Charter of Rights in Records—which are grouped under the heading Participatory Rights in Recordkeeping.

- The right to a comprehensive and authentic record

- The right to additional support where historic records have been lost, are incomplete, or inadequate.

- The right to contribute to the record

- The right to challenge, correct or complete childhood records

- The right to control the use of personal records

However, in revisiting these 5 rights, I was struck by the realisation that we don’t give sufficient attention to the key words in those rights claims:

- What is a comprehensive and authentic record?

- In what ways are records incomplete or inadequate?

- How does a Care leaver best contribute to the record?

- How does a Care leaver challenge, correct or complete childhood records?

- How does a Care leaver control the use of personal records?

I thought then that I should make some comments that give more insight into the context of why I should want to highlight those particular words.

The Australian Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse reinforced two principles about OOHC records—Core Business & Best Interests—that endorsed several of the rights.

Making records is core business

How can you take over the life of a child knowing that you will return the child to her family or send her out into the wide world, without having a duty of making and keeping records about that child? This is not something that social workers, case managers should be doing as an afterthought on Friday afternoon while their mind is turning to after-work drinks at the local. It’s an essential requirement of the job.

Records should be made in the best interests of the child

Just as authorities decide to remove a child from her family in the best interests of the child, so records should be also be made with the same ethical frame of reference—that is, the best interests of the child. This is a concept long promoted and marketed, but not always well understood or applied.

Many records, for example, show that authorities didn’t think it important to keep alive the prospect of future reunion or reconnection with family. The records were never envisaged as an important resource to that end. Yet that surely is a paramount consideration of the principle: best interests of the child.

The mismatch between what was recorded & what is needed now

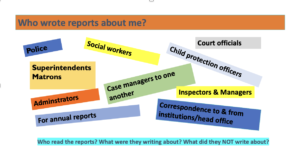

Care leavers learn from reading their files about events in their childhood that they were essentially written by superintendents, police, court officials, social workers, case managers, child protection workers, or are found in correspondence between agencies, for a particular audience, administrators, welfare officials, professional peers and colleagues for exclusive use by welfare officials at a particular time for a particular purpose.

Records were never written with the intention that the subject children would ever read them at the time, or many years later. The writers of records never thought of themselves as writing for a time when the children became adults.

It’s not surprising that many Care leavers find it shocking and painful to read what was recorded. The Royal Commission confirmed what Care leavers have learned: records “regularly contain inaccuracies, inconsistencies, and indeed on occasions absolute omissions” (Transcript Case Study 30, 17 August 2015, p. C8820).

There is something like an out-of-body experience to read a file about yourself as a child. Many Care leavers express their reaction to reading their file: “Got my file, but that’s not me”. We are so often embodied in records as the problem. Not a child with needs, love, hope, nurturing. Just the child as problem.

We Care Leavers have a very different view of our childhood from the one that is our records. My official record, to take one small example, declares that my father’s periodic visits upset me; but I know the opposite was the case. I was never asked for my view or opinions on anything in my 4,397 days and nights as a Ward of the State. When Care leavers see what was recorded about themselves, they deeply regret that they were never given the opportunity to write ‘their side of the story’. As one Care Leaver said, “When we get access to our files we notice everything written about us was by other people …”

Can you imagine what this man, now in his 70s, makes of the psychologist’s report that was written about him when he was 16 years old, at a Victorian detention centre?

The boy was very defensive and cautious in his replies so that not much validity could be attributed to the interview data … His primitive infantile needs of which undifferentiated aggression is the most predominant one are bottled up in him owing only to his mistrust and his suspicious attitude towards society…Although his heterosexual adjustment appears to be inadequate no homosexual tendencies were indicated (Confidential file note).

Once you pick up your jaw, you can simply ask, how did that help the boy?

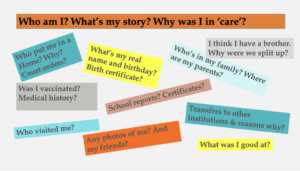

It is not just about the discrepancy between what was recorded in writing and what Care leavers remember about their childhood. Care Leavers come to their records with many questions they want answers to, like:

The mismatch between those questions and the records that were made and what Care Leavers need is the nub of a major problem. And that problem could have been avoided by any of the following:

- Asking the child what they were thinking and feeling and listening to what they said

- Giving them the chance to record their point of view of all the critical incidents that happened in their lives

- Requiring all those people who wrote things about a child to be accountable for what they wrote.

Care leavers were disappointed that the Royal Commission did not deal adequately with two further interlinked questions: the ownership of records and the participation of children in making the records. These questions go to the bigger question: Who’s history is it, anyway?

Two Unresolved questions: Who Owns the Record? And Who Controls the Record?

As indicated by the common use of the term ‘my file’, Care leavers often assume that, although they did not write them, the records are about them, so they must belong to them. Unfortunately, this is not conceded by records holders with a few notable exceptions.

This issue raises the question: Who owns the past? As things stand, it was the bureaucrats, the superintendents, matrons, police, social workers and case managers who created the history found in the official records. Yet they are far from being ‘objective’ descriptions of ‘what happened’ to children and their families. It is the same class of decision makers, decades later, who insist that they ‘own’ the records, and require us the people who are the subject of the records to formally request to see what was written about us all those years ago.

In my own case, I left the OOHC system in 1953. I was 15 and now I’m in my 80s, I have never been able to get a coherent answer from the Department to the questions: Why do you still have a file about me as a child? What use is it to you? Why not just give it to me and you’ll be done with it? There are moral and legal questions as well as practical answers in the mix.

In my view this discussion should be nested in the broader context of how the authorised accounts of welfare agencies have been self-congratulatory history, in which distorted truths punitive policies and brutal practices masqueraded as benevolence.

Two examples of what I mean by self-congratulatory history

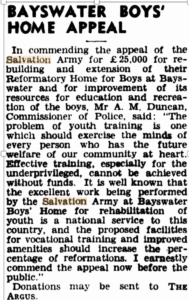

In 1944, the Victorian Commissioner of Police praised the Salvation Army’s work at Bayswater Boys Home as ‘a national service to the country’ (Melbourne Argus, 12 June 1944).

Yet sexual crimes were common knowledge: those in charge knew about it and so did the children. But the scandal was kept from the public. As with the Catholics, more concern about bad press than bad priests. In one notorious case, Salvo high command shifted one officer from Box Hill Home where he had committed sexual crimes to the Bayswater Home because the paedophile’s lived with the “dread that the Box Hill boys would talk with the boys at the Bayswater Home and create scandal”.

I am well acquainted with one former resident of Bayswater, now in his 70s, who sleeps with an axe under his bed, vowing he will never be raped again as he and others had been in that notorious hellhole at Bayswater. His file contains nothing at all about his abuse. As one record holder says, “The chances of a staff member actually recording a complaint made by a child were very slim.’

My second example comes from my own Ballarat Orphanage. Sometimes media gave uncritical voice to unabashed self-serving dishonesty. For example, the Superintendent of the Ballarat Orphanage, Bert Ludbrook, told a conference of the Victorian Children’s Welfare Association in 1944 that “Institutions had made such strides and progress in the last quarter of a century that their environment was equal to that in the average middle class home” (Melbourne Age, 2 June, 1944). And the newspaper printed the story as a serious report.

That is a classic distortion unless middle-class children were neglected, physically and emotionally abused, used as unpaid slaves, and lived in a state of extreme anxiety day and night.

You can understand now why many Care Leavers have given up on historic records and top-down constructions of history. And why so many of them are telling their own stories in their own ways

The ultimate right?

It is pleasing to note that the responsible agency (Cafs in Ballarat) has now removed the name Ludbrook from its headquarters building in Ballarat—and with the collaboration of former residents is constructing a truer history of life in ‘care’. Perhaps that’s the ultimate right—the right to the truth. It’s only on that basis that a Care leaver can make an authentic and coherent account of their childhood.